This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

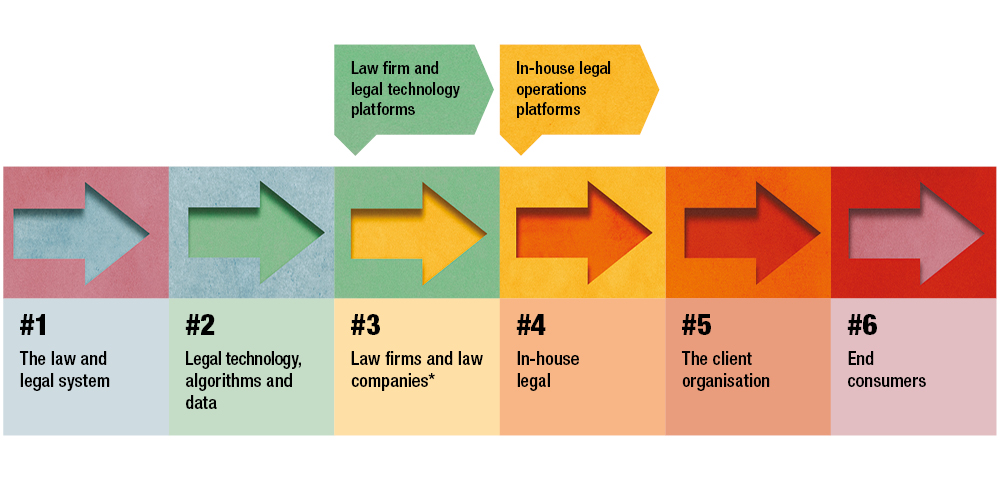

There are six broad entities involved in the delivery of commercial legal services in the modern era: the law and legal system; legal technology, algorithm and data providers; law firms and law companies; in-house legal teams; the client organisations; and end consumers.

Collectively, we can think of these six entities, the value they each add and their interrelationships as the ‘legal supply chain’.

It is important to note that not all legal services involve all six entities; many don’t follow the chain sequentially and some services start and end at different stages. Despite these exceptions, the legal supply chain is a useful conceptual framework, especially to predict the future of lawyers and the legal market.

Prediction 1: Traditional law firms will continue to lose market power

Traditional privately owned law firm partnerships have been at the core of the legal supply chain for well over 100 years. Their market power has been primarily based on the asymmetry of knowledge between provider and client and regulated barriers to entry.

Over the past three decades, the dominant position of traditional firms has been partially eroded by the rapid growth of in-house lawyers. To illustrate, the number of Australian lawyers working in-house grew by 69 per cent from 2011 to 2016 (Source: NSW Law

Society). In-house lawyers have become more sophisticated purchasers and insourced some of the work previously done by private law firms.

Law companies – those providing legal process specialists, managed services and contract lawyering – have become a growing force over the past five to seven years. Recent Thompson Reuters research revealed that law companies had global revenues in excess of $A15.5 billion in 2018, and were growing at 12 per cent per annum.

Legal technology providers are the newest kids on the block, but their growth has been remarkable. Stanford Law School’s TechIndex points to 1051 legal tech start-ups across the globe since 2016, all wanting to be part of the supply chain. Many of these new enterprises are focused on enhancing access to justice by leap-frogging the supply chain to connect end-clients more directly with the law and legal system.

The net impact of the growth of in-house lawyers, law companies and legal technology providers is an equalisation of power across the supply chain. Traditional law firms will still play a critical role, especially in complex and new-to-world cases, but they will no longer dictate market rules and pricing.

Prediction 2: Many lawyers will become value-added resellers

Fast forward fi ve years, and legal technology will have matured to the point that it will become integral to legal advice and delivery. Many commercial lawyers will become value-added resellers of sophisticated technology developed by third-party vendors.

To illustrate, Contract Probe software allows users to perform a comprehensive review of draft NDA, service, supply, consultancy, IP license or employment contracts within 60 seconds for a fixed fee of $100 or less. Created by former Allens TMT partner, Michael Pattison, Contract Probe generates an overall quality score out of 10, highlights key omissions and errors, and makes suggestions for improvement. Contract Probe uses a machine learning approach which means it gets better each time it is used.

In this world, there will be fewer junior lawyers doing the grunt process work but a greater demand for the ‘human’ elements in the client–lawyer exchange; that is, empathy, problem solving, creativity and judgement. Competing as a reseller will require lawyers to have a profound understanding of how the technology works, and how it doesn’t. They will also need to get a lot better at pricing their service to capture value beyond charging for their time. Resellers will live or die based on the depth of their client relationships and their ability to be true trusted advisors.

Prediction 3: Powerful platform providers will emerge

Many law firms are struggling to deal with the avalanche of new applications that are now available on the market. Each of these new solutions is useful in solving a single problem, but firms cannot cope with training and supporting their people in 15 different software tools.

In the United States, the leading firms have formed a collaborative venture, called Reynen

Court, to develop a common platform for legal applications. Chaired by Latham and Watkins and Clifford Chance, Reynen Court will provide common standards, improved inter-connectedness and a more consistent user interface for legal apps. The idea is to make it easy, safe and efficient for major law firms to adopt AI, smart contracts and other new technologies.

In Australia, both PwC Legal and KPMG Legal recently announced collaborations with local providers of legal operations software for in-house legal teams. This SaaS technology provides a single scalable low-cost solution for in-house lawyers to do pretty much everything: transact with external counsel, manage internal workflows, prepare and store documents, service internal clients, communicate value to the C-suite and stay in control of their budget. This technology will allow for ‘plug-ins’ of future AI tools and technologies that are still to be invented. While this software has been around for a while, attaching it to the world’s most powerful B2B brands with deep change management expertise is a game-changer.

Fast-forward ten years and one of the Big 4, or another provider like Elevate or Xakia, will have won the battle to be the dominant platform for in-house legal teams. They will have unrivalled data around law firm performance, pricing, client satisfaction, in-house productivity and a myriad of other benchmarks. They will own the screen of every in-house lawyer giving them extraordinary influence and leverage along the entire legal supply chain.

In this future scenario, this platform owner will become the intermediary that premium law firms, law companies and technology vendors have to deal with. They won’t compete as clones of traditional firms but rather as the Google of the legal world.

A single platform will most likely lower transaction costs and improve choice, quality and responsiveness for client organisations. It won’t displace or disrupt incumbent law firms, but it will most likely reduce their relative bargaining power.

It is worth noting that data security and legal conflict concerns are major obstacles in the way of a single legal operations platform developing. Notwithstanding these issues, the momentum for change in the ‘more for less’ era is significant.

In conclusion

The legal supply chain framework provides a useful lens to predict the future. It can also be used for individual firms to identify specific opportunities or threats. Firms may elect to move backward on the chain by acquiring legal technology capability, forward into a form of managed services, vertically by becoming more dominant in their step in the chain, or tangentially by morphing into or partnering with a platform provider. What’s clear is that the strategic choices open to firms are more numerous and profound.

Supply chain analysis also shows that the consequences of the ‘do nothing’ default option are becoming more significant. Every firm should be deliberate and considered about its choices of where it plays along the chain and how it can win.

Joel Barolsky is Managing Director of Barolsky Advisors, Senior Fellow of the University of Melbourne and Creator of the Price High or Low app

This story was originally published in Proctor September 2019.

Share this article