The Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (QCAT) – the tribunal legislatively tasked with administering enduring document disputes and guardianship appointments – is drowning with upwards of 15,000 new applications each year.

This, compounded by the COVID crisis, has seen up to seven-month waits for preliminary hearings. The tribunal’s purpose is to facilitate swift, accessible, and affordable outcomes. Many of these applications will be due to disagreements between or about decision makers appointed under enduring documents.1 It is arguable that a large proportion of those applications have sought QCAT’s intervention without reasonable consideration of less formal or restrictive avenues.

At the inception of the Powers of Attorney Act 1998 (POA), the legislators anticipated that disagreements may occur between formal decision makers. Section 79 created a proactive obligation for decision makers to consult each other regularly, to ensure the principal’s interests are not prejudiced by a breakdown in communication.

The Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 continued this, with sections 40-43, providing that decision makers must consult each other, and that if disagreement between the decision-making parties eventuated, they were to pursue a dispute resolution path, including mediation, prior to considering a QCAT intervention.

Further, the Public Guardian’s function includes mediating and conciliating between decision makers and others (such as health professionals), where appropriate.2

In fulfilling their duties, attorneys are required to have a good appreciation of the appointing document, and use any term, direction and guidance it may provide to resolve disputes. Decision makers should inform themselves of decision-making principles contained in the POA to learn how decisions should be made; also key is the obligation of attorneys to seek counsel from relevant experts as to the best way forward.

In the aged care, health, and disability sectors, a family meeting may be convened, perhaps led by a social worker who is commonly a member of the treating team. This may go some way to facilitating a decision, but it is important to recognise that all the parties, including the social worker, will have an agenda and not be independent, and they may be swayed by contrary agendas that differ to the principal’s.

In other words, the principal’s views and preferences may not be central to the ongoing agenda. This needs to be made explicit and the ultimate focus in resolving disputes and planning an outcome.

Once informal discourse has been considered, a way forward might be to seek a formal meeting with an independent facilitator or mediator. This should aim to reduce the unresolved areas of conflict, provide clarity as to each party’s objective and position, and also provide education on their roles and responsibilities.

Unlike dispute resolution processes in corporate settings, where commonly both/all parties are of fairly equal footing, and people can often remain at arm’s length from outcomes, dispute resolution in this personal decision-making space has unique challenges.

It must be remembered that the decisions are about a person and their life, and are understandably extremely personal and important to them. They may live or die by the decision which is made.

It is also important to note that in matters about an adult, there is the presumption of capacity for decision making, enjoyed by all adults unless it is rebutted. Necessarily, dispute resolution must include them, the principal, as much as they wish to be involved; and must give consideration to power imbalances (which may be considerable).

Recognition of the relationships between the parties (which may be multiple), and the ongoing nature of these relationships need to be recognised for their importance to the principal.

It should be acknowledged that many attorneys also bear the responsibility of primary carer, as well as being family and/or friend. The principal, and any other party with possible cognitive impairment, should be provided with independent advocacy and support to attain their maximum engagement.

Importantly, all parties must apply the ‘General Principles’. Sometimes referred to as the ‘road map for decision making’, these ensure the views, preferences and prior decision patterns of the principal are interwoven into decisions, and can be found in the POA, Schedule 1.

A hearing is fraught as people act in unpredictable ways. Some pull their punches and dance around their views; others use this as an opportunity to vent family dirty laundry that bears no relevance to the current issues facing the principal.

As well, and unlike other jurisdictions, independent statutory agencies are always available to the tribunal for appointment as alternatives to people the principal knows or might choose. Most people are overwhelmed, despite the efforts of tribunal members to reduce any anxiety or distress; and often parties leave the hearing without any real understanding of the outcomes, or their consequences, or their viability. Subsequently, not all appointments and outcomes are successful.

Remembering that the Public Guardian’s functions include mediation to parties, but recognising their limited resourcing and necessary focus on investigations and decision-making appointments, it should be considered whether they appoint affordable external mediators at a cost to be borne by the active parties or funded by targeted state government funding in order to fulfil their functions and to reduce the burden on the tribunal of avoidable applications.

This would be analogous to the family law mediation jurisdiction.

Given the deluge of applications to QCAT, and the increasing ageing population, it is timely that we consider alternatives to QCAT applications as a way to solving some of the disputes currently lodged there. A practical step may require consent to an externally mediated decision by the Public Guardian’s Pre-Advocacy Team, which already operates in this space between applications to QCAT and ultimately, a hearing.

Then, if attorneys are still stuck on how or what to decide, they could finally consider a path to the tribunal. Within the tribunal process, it is recommended that the applicant consider a request for a compulsory conference at first instance.

A compulsory conference is QCAT’s model for mediation, overseen by a trained tribunal member.3 It is incumbent on the tribunal to ensure the adult is given every opportunity to engage and participate fully, and the appointment of a representative should always be considered.

The representative has obligations to consider the principal’s interests and opportunities, along with their views and preferences, which requires the representative to have a reasonably thorough understanding of their network and service supports. Whilst this role can be of great assistance to the principal and any ultimate decision makers, the time taken over and above an ordinary legal advocacy role is both substantial and unfunded.

Following these two steps above, a tribunal hearing in these circumstances would truly be last resort.

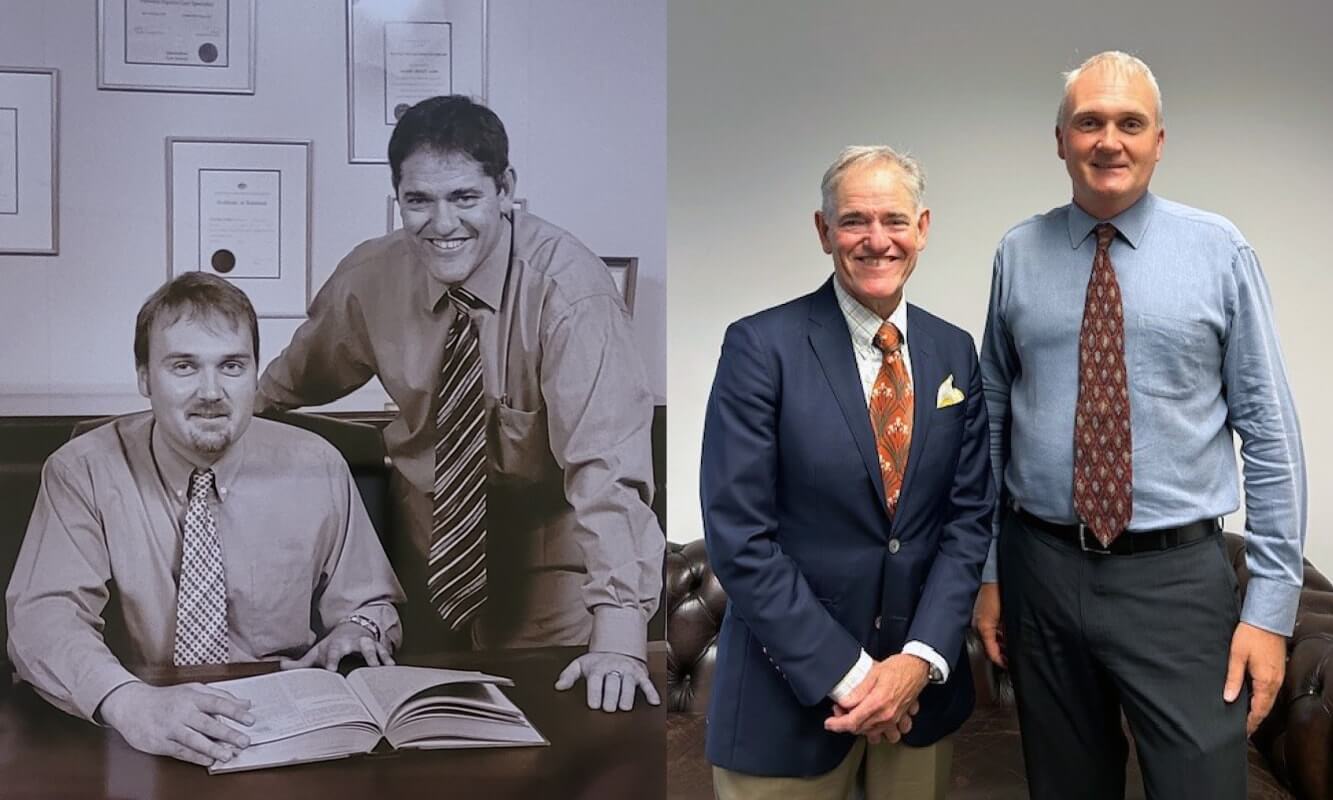

Rebecca Anderson is the Chair of the QLS Elder Law Committee and a solicitor at ADA Law. Karen Williams is Deputy Chair of the QLS Health and Disability Law Committee and Principal Solicitor at ADA Law.

Footnotes

1 In Queensland, the Power of Attorney Act 1998 provides for the execution of “enduring documents” – Enduring Powers of Attorney and Advance Health Directives. Apart from financial decision making that can be operational immediately, for health and personal decisions, the decision-making powers begin when the principal no longer has decision-making capacity for the matter.

2 Public Guardian Act 2014, s12.

3 Queensland Civil and Administrative Act 2009 details a range of dispute resolution processes, along with mechanisms for recording settlement of disputes.

Share this article