“Many of us take it for granted that our first experience with books will be in the language we speak. But this is not the everyday experience for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who speak Indigenous languages, traditional languages or a ‘new’ language like Kriol.”

— Denise Angelo, linguist/literacy consultant on Binjari Buk series, Australian National University.

If there was just 100 people in the world, 14 of them would not be able to read or write.

In 2018, this equated to 1.05 billion people – the equivalent of the combined populations of North and South America – not being able to read or write!

Today, some 250 million children are failing to acquire basic literacy skills, with current statistics showing that 56% of primary school students are not reaching minimum proficiency in reading and maths.

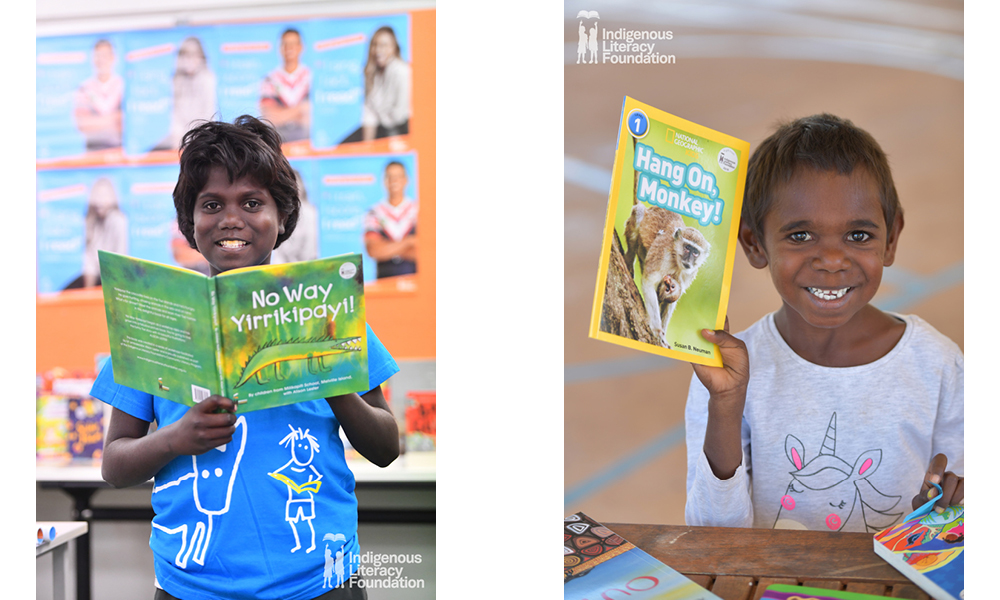

Today, 2 September, is Indigenous Literacy Day, an annual day organised by the Indigenous Literacy Foundation to celebrate Indigenous culture, stories, language and literacy.

Indigenous cultures have existed in Australia for at least 60,000 years and exhibit many fluent aspects that deserve celebration and acknowledgement. While COVID-19 and its current impact on Australia has limited potential celebrations, there are many Australians who will acknowledge this day and celebrate a multitude of unique literacy programs working specifically in the national Indigenous space.

There are also many at all levels of the community and government who are focused on the overall plight of Indigenous Australians and their disproportionate circumstances in current Australian society and are designing policy platforms and strategies to elevate it.

The social and economic disadvantage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australian society is extensive, and achieving social, political and economic parity for Indigenous people with non-Indigenous Australians remains an important and enduring struggle. The continuing impact of intergenerational transfer of multiple disadvantage and welfare dependency suffered by Aboriginal people is a significant stain on our country’s socio-economic status.

Indigenous Australians experience significant disadvantage across almost all aspects of life including health, employment, education and the criminal justice system (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 2005) and ‘closing the gap’ is considered one of the most significant socio-economic challenges facing our society.

To celebrate a national literacy day is to shine a light on the power of literacy. Literacy is so fundamental to learning that its importance cannot be overstated – it is the essential foundation of education.

The Director-General of UNESCO, Audrey Azoulay, said on International Literacy Day in 2018:“Literacy is the first step towards freedom, towards liberation from social and economic constraints. It is the prerequisite for development, both individual and collective.”

This statement mirrors the social and economic intent of the foundations of the ‘Close the Gap’ campaign, its intricate ambitions, and its journey to realise the power of literacy. The target to halve the gap for Indigenous children in reading, writing and numeracy within a decade (by 2018) has driven improvements in these foundational skills, but more progress is required.

Two of the continuing targets are on track.

- having 95% of Indigenous four year olds enrolled in early childhood education by 2025.

- halving the gap for Indigenous Australians aged 20 to 24 in Year 12 attainment or equivalent by 2020.

However, the target to close the gap in life expectancy by 2031 is not on track.

Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. It is in this context that, while we celebrate national Indigenous Literacy Day, it is also pertinent to showcase the stated 2020 Closing the Gap Report statistics on indigenous literacy rates.

What does the Indigenous literacy gap mean?

Only 36% of Indigenous Year 5 students in very remote areas are at or above national minimum reading standards, compared to 96% for non-Indigenous students in major cities, according to the 2018 National Assessment Program for Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN).

Literacy rates among Aboriginal students are lowest in remote communities. Reasons include low literacy of the parents and poor school attendance. Apart from the historical, health, social, and educational disadvantage issues, many remote communities don’t have many, if any, books. In most of the remote communities in Australia there are fewer than five books in family homes.

When we talk about ‘literacy’ we assume we mean literacy of the written word. It is noteworthy, though, that many Aboriginal people were, and are, masters of oral literacy. Oral traditions substantiate Aboriginal perspectives and Torres Strait Islander perspectives about the past, present and the future.

Indigenous language endangerment is critical in Australia, with only 120 of 250 known languages remaining, and only 13 considered strong. A related issue is the gap in formal education outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people compared with other Australians, with the gap wider in remote regions.

Little empirical research exists in Australia to explore the role of developing Aboriginal literacy through bilingual education to address these combined issues. However, existing evidence demonstrates the importance of strong relationships between community and schools.

Further, learning about culture and learning literacy in one’s first language in schools to develop Aboriginal literacy, is established as a necessary step to improve English literacy in remote schools. This suggests bilingual education and strengthening culture and community involvement in schools are necessary to improve both education outcomes and language preservation.

Inclusive education is based on the belief that all students have the right to be educated in regular classrooms, regardless of gender, ethnicity, social class, or ability successfully progressing through and transitioning from school is important for children to improve social mobility and intergenerational outcomes. Inclusion is also a central philosophy in schools, and its educational and social desirability is widely regarded as integral to successful school and classroom practice and therefore should be carried out in all educational environments.

We need to stop making excuses for poor school education in communities and to start learning from what is working, inside and outside communities.

There is compelling research that shows the benefit for Indigenous students with special educational and cultural needs when educated with their peers. In this evolving global environment, we as educators and key community stakeholders need to continue to demonstrate a joint commitment to providing a security of culture and identity and the best educational outcomes for all Iindigenous students, which is necessary for the continuing growth of this nation’s social and educational capital.

Paul Paulson is Queensland Law Society Cultural Consultant.

References & citations

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner. (2005). Social justice report 2005. Sydney: Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission.

Holland, C. (2016). Close the Gap: progress and priorities report 2016. Canberra: Close the Gap Campaign Steering Committee.

Council of Australian Governments. (2009). National Indigenous reform agreement (closing the gap). Canberra: Council of Australian Governments.

Source: Aboriginal literacy rates – Creative Spirits, retrieved from creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/education/aboriginal-literacy-rates.

Wilson, B, Quinn, SJ, Abbott, T et al. The role of Aboriginal literacy in improving English literacy in remote Aboriginal communities: an empirical systems analysis with the Interplay Wellbeing Framework. Educ Res Policy Prac 17, 1–13 (2018). doi.org/10.1007/s10671-017-9217-z

Closing the Gap Report 2020, © Commonwealth of Australia 2020 ISBN 978-1-925364-29-3 Closing the Gap Report 2020 (Print)

“How important is literacy to education and development?” Bridge: 13 November 2018

2017 Indigenous Expenditure Report Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Indigenous Literacy Foundation: indigenousliteracyfoundation.org.au/

healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/learn/health-system/closing-the-gap/history-of-closing-the-gap/#aihref1

‘Indigenous education gap stands out in latest NAPLAN results’, SBS/NITV 2/12/2015,

sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2015/12/02/indigenous-education-gap-stands-out-latest-naplan-results, retrieved 4/12/2015

‘Literacy just doesn’t gel for some Indigenous students – but we have found solutions’, Erica Glynn, The Guardian Australia, 30/7/2017

‘Literacy program teaching Aboriginal adults to read and write’, SMH 29.7.2018

‘NT remote students are failing the basics’, Koori Mail 460 p9

‘Study details test gap’, Koori Mail 423 p56

‘NT data paints a grim picture’, Koori Mail 430 p7

‘Mobile pre-schools seen as NT solution’, Koori Mail 430 p55

‘Literacy, numeracy ‘going backwards”, Koori Mail 398 p73

Koori Mail 385, p60

‘Karijini Mirlimirli’, Noel Olive, Fremantle Arts Centre Press 1997 p102

‘Women talk leadership’, Koori Mail 431 p17

‘Study finds our children really count’, Koori Mail 435 p45

‘Web site shows the way’, Koori Mail 515 p36.

Share this article