This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

Queensland Law Society wrote a submission1 to the parliamentary Legal Affairs and Safety Committee in relation to its inquiry into the Police Powers and Responsibilities and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021 (Qld), which was passed on Tuesday.

A contingent from QLS, including this writer, appeared as a witness at the public hearing held on 15 October 2021 in relation to the inquiry. Although QLS’s written submissions discussed various aspects of this Bill, most concerning for the Society and this writer were the proposed restricted prisoner declarations.

What is the restricted prisoner declaration framework?

Restricted prisoner declarations form a part of the Government’s new framework for parole decisions about a life-sentenced prisoner who has committed multiple murders or who has murdered a child (restricted prisoner).

The Act confers a discretion on the President of the Parole Board to declare that a restricted prisoner must not be considered for parole for a period of up to 10 years (restricted prisoner declaration).2

In deciding to make the restricted prisoner declaration, the President must be satisfied that it is in the public interest to do so,3 and have regard to the following matters:4

- the nature, seriousness and circumstances of the offence, or each offence, for which the prisoner was sentenced to life imprisonment

- any risk the prisoner may pose to the public if the prisoner is granted parole, and

- the likely effect that the prisoner’s release on parole may have on an eligible person or a victim.

The new framework also sets a higher threshold for the granting of exceptional circumstances parole to prisoners subject to a restricted prisoner declaration. Where a restricted prisoner declaration is not made, the new framework creates a presumption against parole such that the onus is placed on the prisoner to demonstrate they do not pose an unacceptable risk to the community.5

The presumption is set against parole unless the Parole Board is satisfied that:6

- Due to a diagnosed medical condition, the prisoner is in imminent danger of dying and is not physically able to cause harm to another person.

- The prisoner has demonstrated that they do not pose an unacceptable risk to the public. And

- The making of the parole order is justified in the circumstances.

The stated purposes of these reforms are to further protect the community from offenders who have committed some of the most serious crimes, and to prevent the trauma and re-victimisation associated with parole applications.

We can all agree that these are noble goals. However, there is an absence of evidence to suggest that these reforms will in fact achieve that.

What are the human rights issues with this framework?

It was argued by the writer that the Bill in its proposed form was a flagrant breach of the Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) (HR Act) in two respects.

First, the restrictive prisoner declaration is effectively a form of retrospective punishment for a crime committed a decade ago. It effectively adds to the prisoner’s original sentence by extending their parole ineligibility past the date set by the sentencing judge. This is contrary to the HR Act, which provides that:

- a person should not be punished more than once for an offence,7 and

- a penalty must not be imposed on any person that is greater than the penalty that applied to the offence when it was committed.8

Secondly, the Bill does not prevent the President from making consecutive restricted prisoner declarations, meaning a person could be subject to arbitrary and indefinite detention.

Arbitrary and indefinite detention without the prospect of release can amount to inhuman treatment, which is contrary to ss17(b) and 30(1) of the HR Act. It is also a breach of longstanding international human rights jurisprudence9 and it is contrary to the intent of the judge who actually sentenced and set a parole eligibility date at a particular point in time.

It was argued by the writer that such a drastic change to the criminal justice system, which retrospectively punishes people indefinitely or for rolling 10-year periods, has to be demonstrably justified and it has to be based on evidence.

Although the Government’s stated intention of avoiding re-traumatisation of victim families is a legitimate one, there is no evidence to suggest that the proposed Bill would achieve it. Therefore, the committee was urged to not recommend the serious offender declarations framework to Parliament.

However, were the committee to recommend the framework, it was argued that the right to fair hearing must be given due consideration. In the Act, the right to fair hearing is limited, as the decision to make the serious offender declaration is not made in open court by a judicial officer, but rather behind closed doors by the President of the Parole Board.

Although it is not suggested that the President is not sufficiently independent, the process is not public and does not involve a hearing where the prisoner can speak to their parole eligibility. A better and fairer process is required to ensure that prisoners’ right to fair hearing under the HR Act is protected.10

For example, a better process would be an application to a Supreme Court Judge in a similar way as under the Dangerous Prisoner’s (Sexual Offender’s) Act 2003 (Qld). This would ensure that the person in detention has:

- proper legal representation

- an adequate opportunity to see the evidence that may justify their indefinite detention, respond to the evidence, call evidence and experts, and

- a hearing and decision in an open and transparent manner regarding the imposition of such an onerous retrospective form of punishment.

In its report, the committee stated that the introduction of restricted prisoner declarations may be incompatible with the right to be free from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and the right to humane treatment in detention.11 The committee specifically acknowledged the following aspects of the Bill as being potentially incompatible with human rights:12

- the potential for a declaration to be made which precludes the prospect of release despite the prisoner achieving rehabilitation during the term of the declaration

- the prospect of ‘rolling’ declarations being made, which would deny a life-sentenced prisoner the possibility of ever being released, and

- for prisoners who are currently serving life sentences, the amendments alter the conditions on which they may be released, which is incompatible with the proposition (accepted by the European Court of Human Rights) that a prisoner is entitled to know “at the outset of [their] sentence” what they must do to be considered for release, and under what conditions, including when a review of their sentence would take place, or could be sought.

The committee referred to the case of Minogue v Victoria13 and made positive reference to “the principle that all prisoners, including those service life sentences, be offered the possibility of rehabilitation and the prospect of release if that rehabilitation is possible”.14

Furthermore, the committee acknowledged that, despite numerous references to the stress and trauma suffered by victims’ families and friends, and possibly the wider community, no evidence was provided to support these concerns.15

This was contrasted to the concrete nature of the harms suffered by prisoners who are denied the opportunity to see parole, such that the harms formed the basis for challenges to the highest courts in numerous international jurisdictions.16 The committee further questioned the rational connection between the Bill and the secondary aim of community protection, since no explanation was given as to why an additional barrier was necessary.17

Despite these comments by the committee outlining issues with human rights compatibility, the committee cited the ability of the Government to make an “override declaration” to remove the application of the HR Act with respect to restricted prisoner declaration,18 and recommended that the Bill be passed in its entirety.19

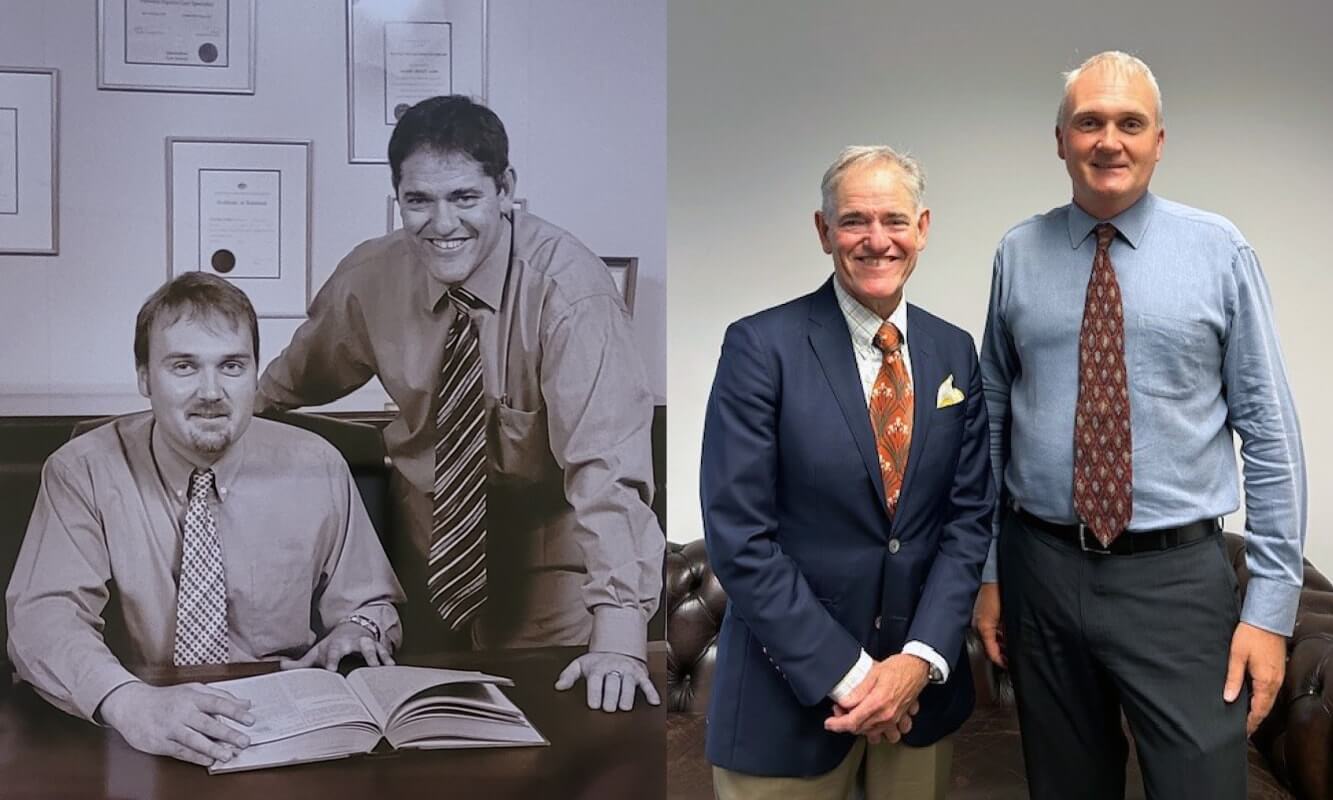

Dan Rogers is a Principal and Legal Director of Robertson O’Gorman Solicitors. He is also the Chair of the QLS Human Rights and Public Law Committee.

Footnotes

1 Read the submissions of QLS and other entities to the committee.

2 Police Powers and Responsibilities and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021, cl.7 s175E.

3 Ibid cl.7 s175H(1).

4 Ibid cl.7 s175H(2).

5 Ibid cl.12 s193AA(5).

6 Ibid cl.7 s176A(2).

7 Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) s34.

8 Ibid s35(2).

9 See, for example, Vinter v UK (2013) ECHR 645, 114. Cited in Minogue v Victoria (2018) 264 CLR 252, [53], [73].

10 Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) s31(1).

11 Legal Affairs and Safety Committee, Parliament of Queensland, Police Powers and Responsibilities and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021 (Report No.15, November 2021) 40 (Report).

12 Ibid 36.

13 (2018) 264 CLR 252.

14 Minogue v Victoria (2018) 264 CLR 252, [53]. See Report (n11) 36.

15 Report (n11) 40.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) s43.

19 Report (n11) 1, 41.

Share this article