A recent case1 in the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal has called into question the legality of some administrative arrangements put in place by the Queensland Commissioner of State Revenue.

Administrative arrangements

The Queensland Commissioner adopts the practice of publishing public rulings containing administrative arrangements which extend legislated duty exemptions and even promulgate new duty exemptions not contained in the legislation.

An example of extending duty exemptions is Public Ruling DA000.10.1 Transfer duty – relief for certain trust acquisitions, trust surrenders and partnership acquisitions. This public ruling essentially provides the Commissioner will disregard the express provisions of the legislation and treat trust interests and partnership interests as being dutiable property for the purposes of certain transfer duty exemptions.

To obtain this relief, the taxpayer must apply to the Commissioner. The Commissioner then decides, on a case-by-case basis, whether or not ex gratia relief from transfer duty should be granted. The published criteria to be satisfied to obtain a favourable decision from the Commissioner are that the exemption would apply but for the trust interest or partnership interest not being dutiable property and that the Commissioner is satisfied it is appropriate for the exemption to apply.

An example of making new duty exemptions is Public Ruling DA000.16.2 Administrative Arrangement – duty exemptions for eligible small business restructures. This public ruling expressly provides the Commissioner will administer the duty legislation as if the legislation contained the relevant exemptions.

To access these new exemptions, the taxpayer must apply to the Commissioner. The ruling does not say ex gratia relief from transfer duty will be granted, just that the Commissioner will assess duty on the basis the exemptions are law.

The VCAT case

Duty was assessed on a transfer of farming land from a farmer to a property trust the sole beneficiary of which was the farmer’s self-managed superannuation fund. The corporate trustee of the property trust was solely controlled and owned by the farmer. He was the sole member of the superannuation fund and the sole director and shareholder of its corporate trustee.

He transferred the land as part of his retirement and succession planning – he had made a binding death benefit nomination in favour of his two daughters so that his farm would stay in the family.

For the Victorian family farm exemption to apply, the transferee must be:

- a relative of the transferor

- a fixed trust having beneficiaries limited to relatives and/or charities, or

- a discretionary trust which did not allow capital distributions to persons other than relatives and/or charities.

The transferee property trust was not any of those entities.

The farmer submitted the Commissioner should extend the exemption to encompass the farmland transfer as it met the “spirit” and “intent” of the legislation and was in accord with the policy purpose of the exemption.

Unfortunately for the farmer, this submission did not meet with any success.

The tribunal held the Victorian Commissioner did not have a discretionary power to waive or reduce the duty assessable by extending the “family farm” exemption.

The Queensland Commissioner’s authority

What legal authority does the Queensland Commissioner have to make and implement the administrative arrangements?

It’s the vibe of it. It’s the constitution. It’s Mabo. It’s justice. It’s law. It’s the vibe and ah, no that’s it. It’s the vibe. I rest my case.

The Castle – 1997 Australian comedy movie.

The constitution

Regardless of the Commissioner’s powers, the Queensland constitutional position is that taxation can only be imposed by legislation – not by administrative arrangement made by a government officer.

The power of the State of Queensland to impose taxation, subject to the operation of the Commonwealth Constitution, is regulated by the constitutional precept, accepted as settled since the fourth declaration contained in the Bill of Rights 1688 or 1689, that taxation must be imposed only under the authority of legislation.2

Only the state’s legislature has power to make laws dealing with taxation. This power has not been delegated or entrusted to the Commissioner under the Duties Act 2001, the Taxation Administration Act 2001 or the Regulations made under these Acts (duty laws). The Commissioner’s role is to administer and enforce the duty laws – not amend or make new duty laws.

Mabo

The Mabo3 decision did not empower the Commissioner in any way whatsoever.

Justice

It is submitted that justice and good governance is not promoted by a public service officer4 having the discretionary power to make taxation law by extending exemptions, making new exemptions or granting ex gratia relief from tax to certain taxpayers in certain situations where the officer considers it to be appropriate to do so.

Admittedly the Commissioner’s practice benefits the relevant taxpayer. It also benefits the Commissioner. It is much easier to simply publish a public ruling rather than engage in the parliamentary process required to enact new law. Putting the onus on individual taxpayers to apply for relief also gives the Commissioner a compliance opportunity to require extensive disclosure from the taxpayer.

But the practice leads to some taxpayers being treated differently to others with the taxation outcome being dependent on factors such as the skill or influence of the taxpayer’s representative or the views of the relevant assessing officer.

In addition, aggrieved taxpayers have no path to appeal unfavourable decisions as the published exemptions do not exist at law and any appeal would be futile. Another problem is that the self-appointed discretionary powers could be used arbitrarily, capriciously, inconsistently or for ulterior purposes. It is not suggested this is happening, only that it is possible.

A taxpayer’s obligation to pay tax should be clearly spelt out in legislation and not determined on application to, and at the discretion of, a government officer. There is no justice in taxation by decree with relief given on a case-by-case basis. The rule of law is paramount, always.

The law

The duty laws do not give the Commissioner any specific express powers to extend duty exemptions or make new exemptions.

The Commissioner’s function is to administer and enforce the duty laws.5 To do this, the Commissioner must only exercise powers given under the duty laws which include the power to do all things necessary or convenient for performing the Commissioner’s function.6

It goes without saying the Commissioner is attempting to legislate new tax laws by extending exemptions or making new exemptions. This is not the Commissioner’s function. The Commissioner’s legislated function is to administer and enforce the tax laws as legislated. The Commissioner has no power to amend the duty laws or make new duty laws.

The vibe

What is left to justify the Commissioner’s practice?

It’s the vibe of it.

It’s the expediency of implementing what the Commissioner considers to be good policy or achieving what the Commissioner considers to be good taxation outcomes based on the Commissioner’s view of policy rather than the law.

But, as argued above, the practice breaches the rule of law and does not promote good governance.

And there is a simple remedy – if the law needs fixing, legislate.

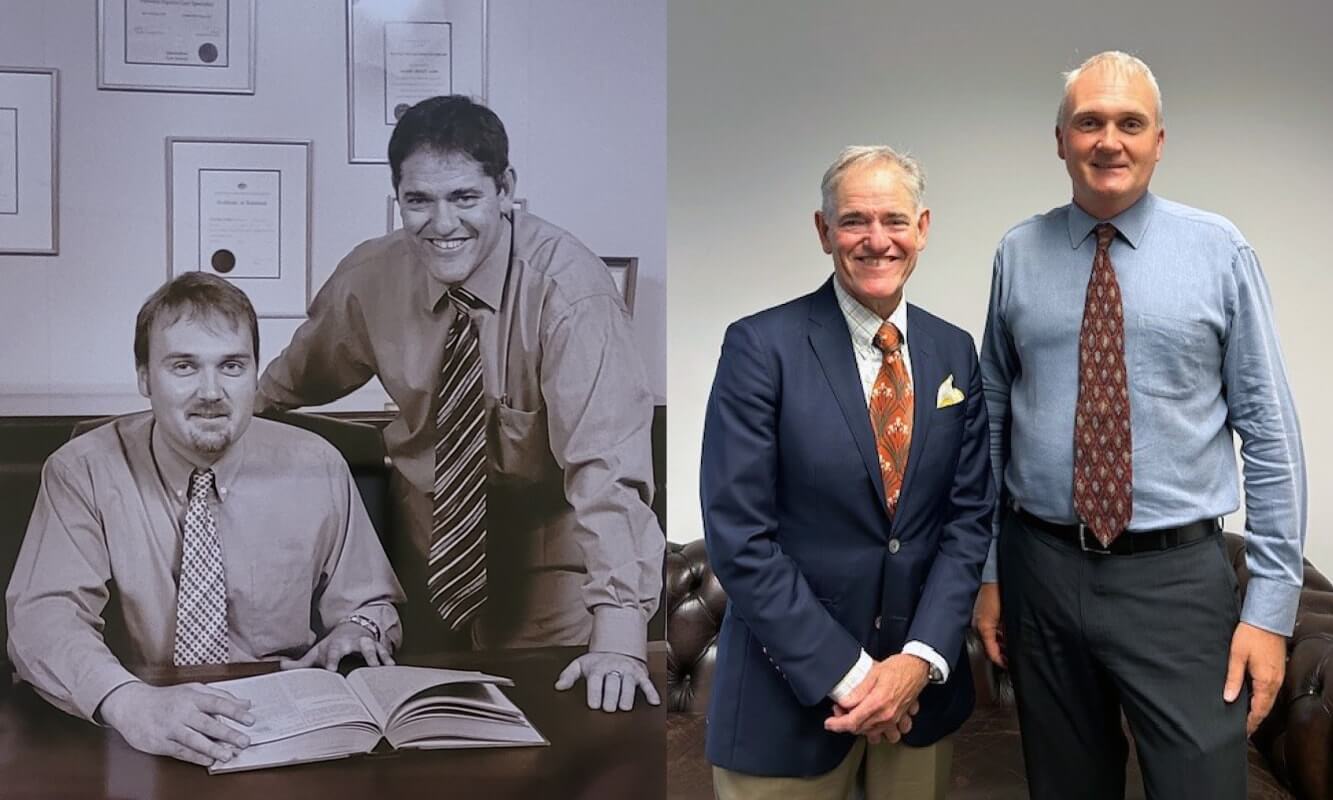

Vince Bailey is the Principal at Vince Bailey Lawyer, Cairns. Any opinions expressed are those of the author.

Editor’s note: The issues identified in this article have been the subject of QLS correspondence to the Treasury, in which QLS recommended legislative reform to address the concerns. See copies of the correspondence, including the most recent letter.

Footnotes

1 ANO Property Pty Ltd v Commissioner of State Revenue (Review and Regulation) [2022] VCAT 71 (20 January 2022).

2 Island Resorts (Apartments) Pty Ltd v Gold Coast City Council [2021] QCA 19 para [37].

3 Mabo v Queensland (No.2) [1991] HCA 23.

4 Section 7 Taxation Administration Act 2001.

5 Ibid, section 8.

6 Ibid, section 9.

Share this article