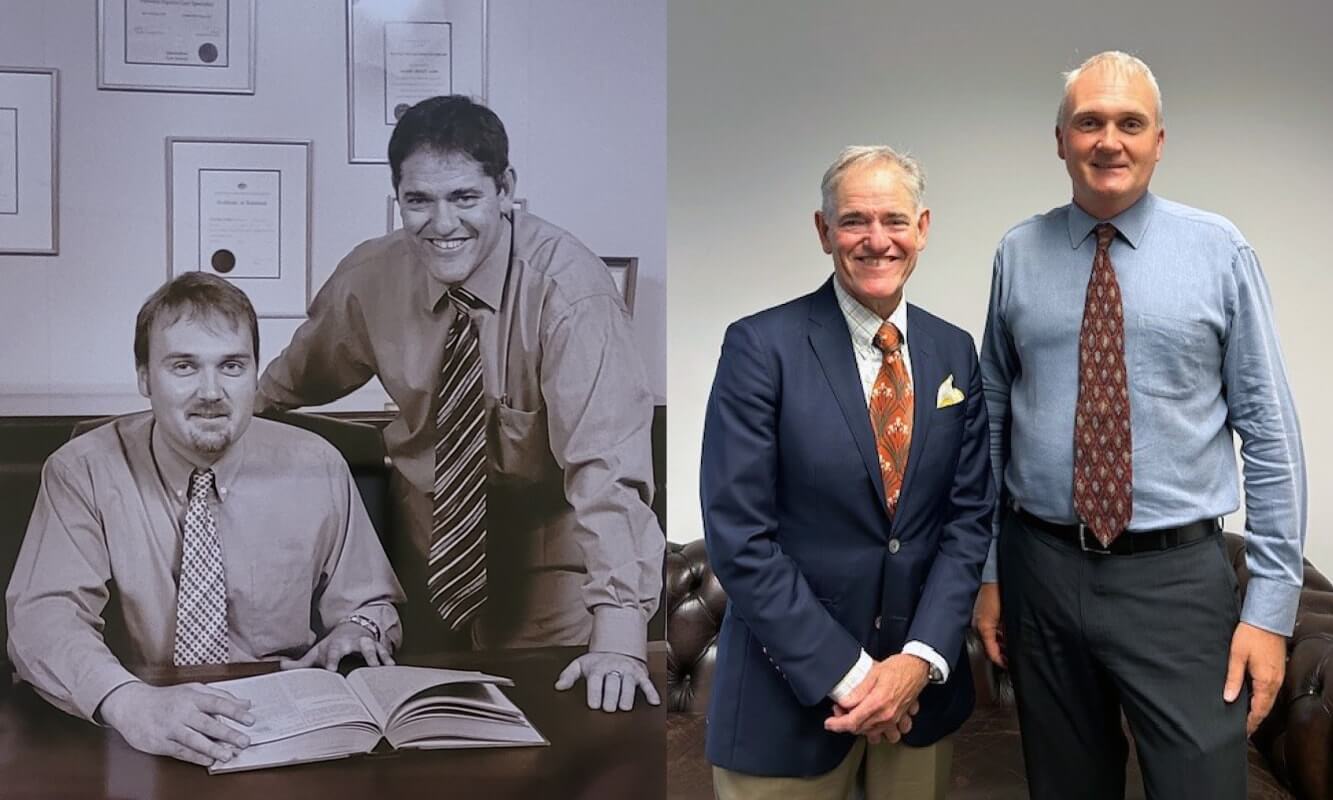

‘Gentleman Jim’ FitzGerald with John de Groot, right.

Fifty years ago this year, Jim FitzGerald left his Brisbane practice of JF FitzGerald & Seymour to form Walsh FitzGerald & Hilton in the new Bank of New South Wales building at 260 Queen Street.

That decade was also to see a shift in the practice of law into a larger, faster, and more frenetic version of itself.

Jim was one of the few solicitors in Brisbane who straddled two eras – the gentlemanly, unhurried old world of the pre-1950s practices of his father and grandfather, and the post-1970s New-York style bustle of modern practice. He finally retired at the ripe old age of 82 in 2007 and could have claimed to have “seen it all”.

Jim came from a distinguished line of lawyers.

Jim’s grandfather, James Francis FitzGerald, was well known in the pastoral industry through his work with the Pastoralists’ Federal Council of Australia during their battles with the Australian Workers’ Union in the early years of Federation. His son (also James Francis FitzGerald but who took his second name Frank) joined him at his firm as an articled clerk and then a partner in 1913.

This brought Frank into contact with the Doneley family. JT Doneley was an imposing figure in the pastoral industry and nephew and right hand to Jimmy Tyson – reputedly Australia’s first self-made millionaire and later immortalised in the Banjo Paterson poem T.Y.S.O.N. Frank married one of Doneley’s daughters, Cecily.

Frank FitzGerald, featured in

The Courier-Mail on 11 May 1938.

Frank had an illustrious career in the law – including two terms as President of Queensland Law Society in 1948-1950.

Jim heard his father recall the common practice within law firms during the First and Second World Wars to accept work from the clients of solicitors serving in the war on the strict condition that the work would be returned to that solicitor upon his return from service. It was not a noble gesture but simply “the done thing” at the time.

It was also considered somewhat “ungentlemanly” to prompt a client for payment of bills.

Rainmaking partners at these firms would socialise and network – the good firms ran off the partners’ guidance and the industry of lowly paid clerks and secretaries. In later years, much of this work would pass to junior lawyers as the male clerks, in particular, moved to other industries in the post-war boom which would more handsomely reward their hard work, and organisational and negotiation skills.

There were no hundred-page documents – agreements were recorded by typewriter with carbon paper to generate a duplicate. These inventions were finally phased out of offices in the latter half of the 1980s along with the people who still used them, the elderly ladies who specialised in probate work.

Frank was a gregarious fellow and, apart from his thriving legal practice, he was vice president of the Queensland Employers Federation, and President of both the Royal Queensland Golf Club and the Brisbane Club.

Frank’s life had numerous tragedies, stellar career aside. In 1930 his youngest son Desmond died at two years of age and, in 1932, his wife Cecily died from rheumatic fever at the very young age of 38. Frank himself passed in 1951 at the age of 62.

Young Jim attended Downlands College in Toowoomba after winning a scholarship in Grade 7.

Downlands was relatively new – coincidentally it was partially built on lands that belonged to his mother’s family. Regardless of its youth, the school produced a golden generation of young men during the ’40s and ’50s, including future Chief Justice of Australia Sir Gerard Brennan, future Chief Justice of Queensland Sir Walter Campbell and many prominent politicians (including two state Premiers), lawyers and doctors.

Jim at 25.

Jim, like his father before him, had been clerked to his father. As a young man first arrived in the city, he would watch General MacArthur’s jeep pull up in Queen Street as the great man himself alighted to his day’s work.

In later years Jim would marvel at the ambition of young lawyers at his firm – he certainly did not feel that he set the world on fire in his early years in the profession. Academically, he crawled through his Solicitor’s Board exams, not being admitted as a solicitor until he was in his early 30s. However, he did enjoy valuable time being mentored by his father.

Jim very much felt in Frank’s shadow throughout his life. Jim said of Frank: “He never went away on holidays, not even for a weekend, without picking up some new business.” Jim learnt much from him and would recount lawyerly sayings of his father, such as “anyone who insists upon a gentleman’s agreement rarely is”.

Jim warmed to his work very slowly but surely. His painstaking attention to detail and a strong work ethic was starting to provide him with some reward.

In his later 30s Jim finally met the love of his life, Judy. They began a whirlwind courtship – Judy was an air hostess at the time and they would catch up briefly at Townsville airport while Judy was passing through – Jim was embarking on the first twin-engine flight around Australia, with his client Fred Marginson and colourful American pilot Max Conrad, who had flown the plane from Pennsylvania.

Jim and Judy married in 1963 and enjoyed 30 wonderful years together before Judy’s untimely passing from cancer in 1994. They had six children together.

In order to finance his Clayfield house and growing family, Jim went to Westpac for a mortgage in 1970. They were keen to fill their new headquarters at 260 Queen Street and agreed to the loan provided he went into practice with Peter ‘Pappy’ Walsh in 260 Queen Street. The firm grew steadily alongside Jim’s burgeoning reputation.

From the late 1970s, Jim gained a good deal of interstate and international work. Business was changing and the profession with it, principally driven by ‘computerisation’ as it was called – word-processing, time-recording, automatic billing and monthly financial statements.

He particularly enjoyed the work from a once-small building company out of Townsville called Kern Brothers, which had turned into a large listed company called Kern Corporation, headed up by a dynamic entrepreneur called Barry Paul.

Kern built many landmarks in Queensland and New South Wales, including the Wintergarden, the Cairns Hilton and Grosvenor Place in Sydney. Jim worked with Barry on Kern’s partnership with a certain New York casino operator called Donald Trump to put a casino in Darling Harbour. Apparently, according to Jim, Mr Trump liked to keep you waiting a whole day in his reception area, never saw you and had one of his henchmen send you a fax later.

Jim’s commercial and legal acumen saw him invited onto the board of Kern.

In 1986 he left Walsh FitzGerald & Halligan, as it then was, to go into partnership with the late Graham Macdonald and Doug Bennett at Kinsey Bennet & Gill. These were the happiest of his practising days – the firm was well run and provided plenty of support for him.

Jim was ambivalent over the new style of legal practice; he loved the technology but was also painfully aware that it greatly increased clients’ expectations of turnaround of work. As he became more productive through experience and technology, the time pressures from clients managed to keep him at the office until past dinner time.

Jim was well suited to the new world. He was a prolific reader and had an equally prodigious intellect. He was not perturbed by the progression of commercial documents from three to 30 to 300 pages, and could pick out errors or issues from an ocean of text. He thrived in complexity and abstract legal principles.

His dictum was that the lawyer was not there to try and make the complex simple – but to make the complex clear.

His letters of advice were a wonderful walk through some very complex subject matters. He would take the reader on a journey, using impeccable grammar, but was never afraid to use metaphors in quotation marks to make his point. The letters were very conversational, without ever being colloquial.

Many lawyers would comment that Jim had “taught them a lesson” about the law of easements or finer points of corporate taxation law. One of his sons recalls one solicitor emailing him:

“Jim would write you a letter. He would state his position. He would then go through all the points you were about to rely on and one by one dismiss them with a very detailed analysis. He would then raise some other points you had not even thought of and dismiss them for good measure. But he was never rude or sharp – it was like receiving a letter from a kindly professor. It was never a short letter either. If Jim had a nut to crack, a sledgehammer was a pretty good tool.”

Jim was a master craftsman with English and had many amusing aphorisms such as “a misplaced colon is as deadly as its diseased namesake in your gut”. He was also a treasure trove of Depression-era colloquialisms such as the mythical Mr Kafoops and the unhappy state of being “spiflicated”.

Above all, Jim was a mentor. He trained many lawyers and was a wonderful mentor to many lawyers who enjoyed Jim’s wise counsel on countless occasions right up to a short time before his passing.

While Jim was not exactly a picture of health throughout his career, he enjoyed a remarkable constitution. In his pomp in the 1980s and 1990s, Jim could outshine many younger colleagues as far as energy and work ethic was concerned – even after two bouts with cancer and a quadruple bypass.

All throughout his career, Jim performed a lot of pro bono work and would often step in to assist with non-legal help as well.

He rarely disclosed much of this work, seeing it as his Christian duty.

When he was admitted to a nursing home in his mid-80s, his desk drawers yielded up a trove of evidence of his kindness his children knew nothing of, such as his volunteer work at Mt Olivet Hospital where he would visit and comfort the dying. They also discovered other items such as letters of thanks for his advice, intervention, or money from people and missions they had never heard of from many different places in the world. Jim was not particularly wealthy in his later years, but he gave what little he had away so many times.

He passed away in 2016 at the age of 91.

In contrast to the modern practice of some firms retiring partners at 50, Jim saved his best work for his 60s and 70s.

He had considerable acumen in commercial law, securities, taxation, stamp duty, advanced Titles Office and Stamps Office work, subdivisional development, trusts, superannuation, and complex wills work – he once remarked that the only areas he had not practised in were admiralty and insurance law, family law and administrative law.

His foot in the old camp was his breadth of practice and the “gentlemanly” approach towards your colleagues in the profession and staff.

In the new camp, he was always adopting the latest productivity technology and marvelled at the knowledge age unleashed by the internet. He was very happy to see the growth in female numbers in the profession. He was less fond of the “New York manners” of some of the younger lawyers.

Jim took a great interest in the opening of the new courts complex in George Street in 2012 and a request was made through friends to the then Chief Justice, to see if he would facilitate a visit. The Chief Justice said that he would be delighted to personally show Jim around and offered car parking and any assistance Jim might need – such was the respect Jim enjoyed in the legal profession.

As a father and a friend, as well as in practice, Jim led by example, not word. One email to his family following his death recounted his nickname within the profession: ‘Gentleman Jim’. Jim was one of nature’s gentlemen, and that is a perfect description of him.

To it could only be added that he was a remarkably accomplished lawyer and the very best person you could ever wish to know.

Patrick FitzGerald is Jim’s son and practised law until 1993 when he left the law for the technology world. He was a founder of dynamicplanner.com in London and now resides in Brisbane. Dr John de Groot is a Legal Practitioner Director and Special Counsel at de Groots Wills and Estate Lawyers, and a Queensland Law Society Past President.

Share this article