This speech was originally delivered at the ‘Justice and the Law Society (University of Queensland) Annual Fundraising Gala’ by Justice Martin Burns in October, 2021. It has been published with permission.

Good evening.

I would like to tell you a story.

When I started out in the law in the early 1980s, several years before the Fitzgerald Inquiry into police corruption, Boggo Road Gaol was not the historical site that most people know it to be today. There was no museum, no ghost tours and no sleepovers for corporate types doing their bit for charity.

Rather, Her Majesty’s Prison Brisbane, as it was formally called, was very much a working gaol and, more than that, it had been the state’s main prison since 1883. In the first 30 years of its existence, Boggo Road was also the place of execution for over 40 prisoners sentenced to death, and in the 70 years or so which then passed before my first visit, its walls bore witness to unimaginable acts of cruelty, deprivations on a grand scale and purposeful misery.

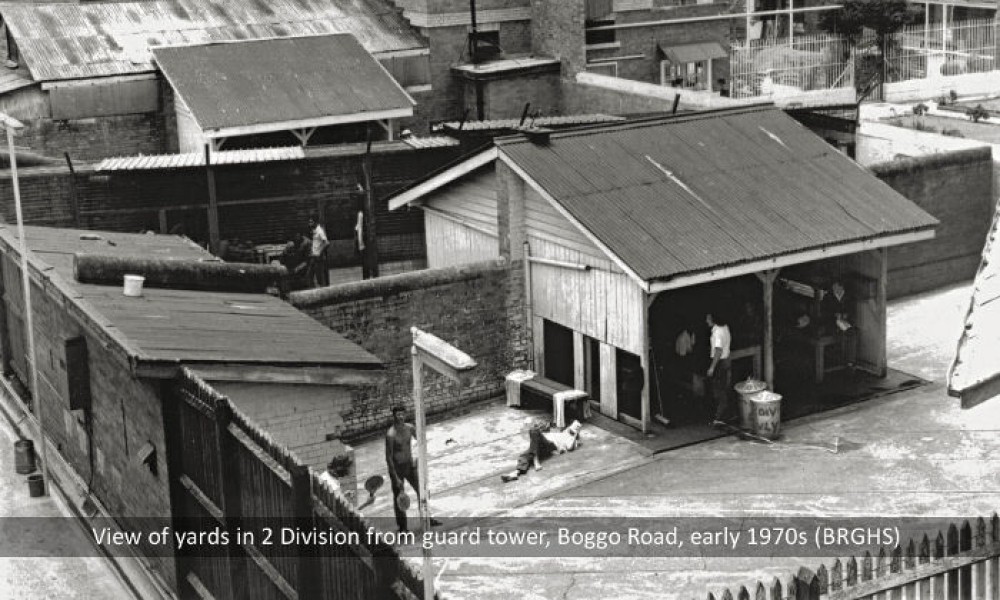

The physical configuration of Boggo Road went through a number of changes during its history but, when I was going out for legal visits, there was a separate women’s prison and two divisions for the male population – Division 1 was used for remand prisoners along with those convicted of less serious offences and Division 2 was reserved for maximum security prisoners.

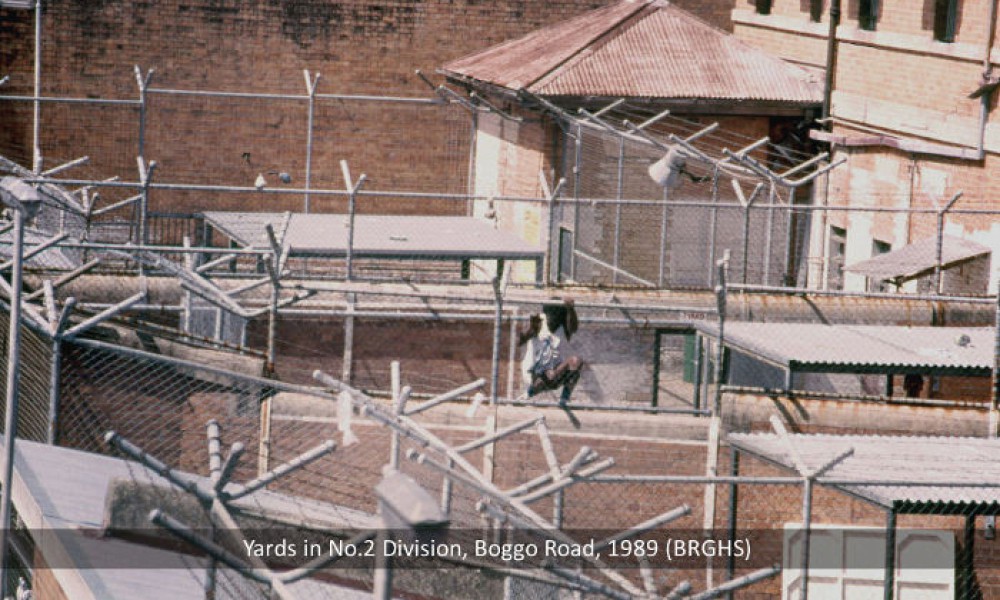

Division 2 yards of Boggo Road in the ’80s. Photo: Boggo Road Gaol Historical Society (Inc.).

Division 2 was notorious, and not just within Queensland. It was well-known among the criminal class interstate as a truly horrible place with a nasty reputation; a place to be avoided at all costs. The conditions under which the prisoners were held were primitive by today’s standards.

There was constant over-crowding. Prisoners slept on thin exercise mats, a shared billy tin was all that passed for a toilet, there was no running water and none of the cells had windows, just ventilation slots near the top of the cell walls. The women’s prison was not much better.

Boggo Road was designed to facilitate the best penological practices the 19th Century could offer, and much of that was focused on subjugation of the prisoner. This was achieved through several means including the regular withdrawal of the few pitiful privileges on offer, cruel forms of summary punishment and real brutality. The whole approach has been described in much of what has been written about this topic as “dehumanising”.

Make no mistake, this was a deliberate strategy and by no means unique to Queensland; it was commonly employed throughout the country. To give you just one illustration of the management practices in vogue at Boggo Road, although there was an oval for exercise, buried underneath part of it was a facility known as the “black hole”.

A trapdoor led to a couple of underground isolation cells which were used to punish prisoners with what was then said to be solitary confinement, but which was almost complete sensory deprivation – prisoners sent there were kept for extended periods in not much more than a cramped, concrete box in complete darkness and with minimal human contact.

Elsewhere in the state, there was just more of the same. For example, in the Townsville Gaol, indigenous prisoners were confined in filthy conditions with around 80 to 90 men crowded into a single dormitory.

Throughout the prisons, corruption was rife, and largely because of that, the then drug of choice – heroin – was widely available. Indeed, heroin was welcomed by some prison officers because it was seen as an effective way of controlling the behaviour of many of the lifers.

Little was offered in the way of rehabilitation. No thought seemed to be given to mental health issues, whether pre-existing or caused through this brand of confinement. Assaults including the gang rape of fellow prisoners were regular occurrences and punishment (or reprisal) beatings at the hands of prison officers were just as frequent. Victims were taken to a rudimentary clinic described more ostentatiously as the “Prison Hospital” to be patched up. Only the worst of medical cases made it out for treatment.

The red-brick facade of Boggo Road, 2012.

So, back in those days, Boggo Road was an intimidating place even for a lawyer to visit. There was a process to be followed in that regard. You would park your car in an open space off Annerley Road but then came a long walk up the hill to the main entrance gate.

I always had a sense of foreboding as I approached that gate. It was hard not to; the prison was ringed by a six-metre-high red-brick wall incorporating the main entrance gate, a gatehouse and an observation tower in the south-western corner. On top of the wall was a catwalk on which prison officers armed with high-powered rifles kept an eye on everything moving below them, inside and out, and including young lawyers fidgeting their way up the hill.

When you made it to the front gate you waited to be processed for admission. To the right of the spot where we all waited was a sign on the prison wall. It read, “Unauthorised persons keep out. Trespassers will be prosecuted”. Now, why anyone within the Office of the Comptroller-General of Prisons thought it necessary to warn people not to break into the prison was a mystery I was never able to solve, but it was the only remotely amusing thing about the whole place.

However, any thought I might have had along those lines would quickly evaporate when I was allowed in and escorted to where legal visits were conducted – a series of “lean-tos” on one side of a quadrangle where you waited for your client to be brought under guard and then had what passed for a conference. Nothing that was said between you could ever be regarded as confidential.

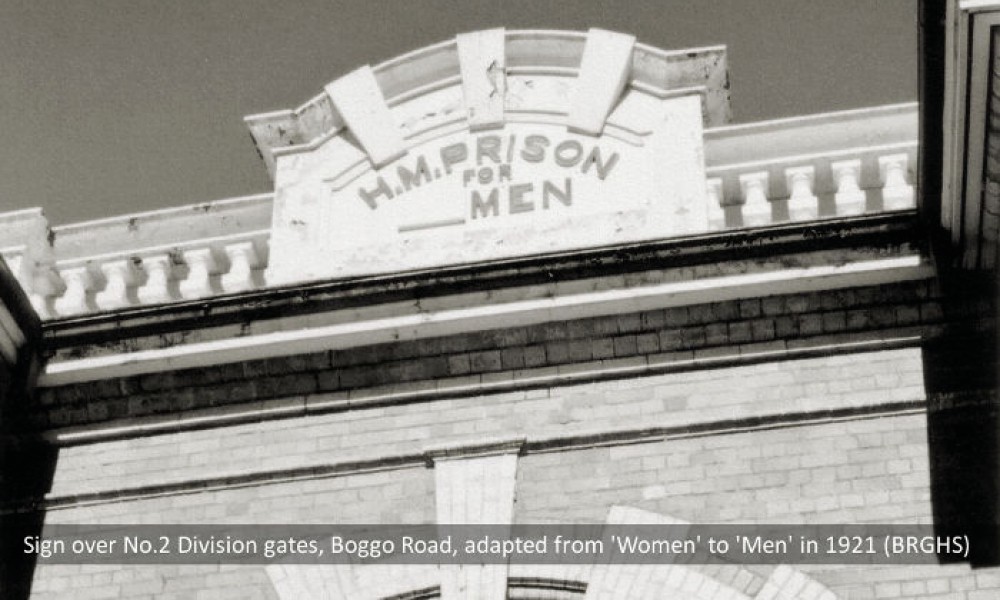

The front gate sign of Division 2 in 1921, adapted from ‘women’ to ‘men’. Photo: Boggo Road Historical Society (Inc.).

So, you might ask: how did we respond to all of that? After all, those working in criminal defence, including me, could not fail to know a fair bit about what went on inside Division 2. Some of my visits were to prisoners who had been held on remand in Division 1 but had just been convicted to long sentences and therefore moved to Division 2. Their fear was palpable. It was, simply, the very last place anyone would want to find themselves. But what, as a young lawyer, did I, or any of the other visiting lawyers, do about it?

Well, in the case of most of us, not much.

Sure, we fought hard in every case to keep our clients out of there but when that fight was lost, off they went anyway.

Employed solicitors such as me were not paid or necessarily permitted to rail against the penal system. We were expected to get onto the next case and most of us did just that, but it was always deeply worrying. Of course, when the occasion arose, formal complaints would be made about the mistreatment of our clients and no doubt we (or our employers) joined at times with segments of the profession practising in criminal law when an issue arose requiring a combined voice.

But, by and large, most of us were encouraged to accept that this was how things were. This was the system we grew up with and now worked alongside. We were often told that prison was not meant to be easy and, on some occasions, fed a line that many of the excesses of which we were aware were just part of the harsh punishment imprisonment represented in those days. This was a large part of the conventional thinking at the time but, of course, it couldn’t have been more wrong.

Inside an ‘outdoor’ cell – exposed to the elements, 2012.

The result, though, had the terrible consequence that, on conviction, prisoners were largely left to fend for themselves. They had no voice and little in the way of rights. For first-time prisoners, they quickly found that they would not just be doing time; it was far worse than that.

The real irony of course was that, when representing them, we did our utmost to defend our clients and to uphold their rights but, on being sentenced to a period of imprisonment, we just vanished from their lives, or at least most of us did. They were left vulnerable and, in most cases, afraid.

But, fortunately, there was change afoot, and that change can be traced to events that occurred around a decade earlier in upstate New York.

In 1971, nearly 1300 prisoners took over the Attica Correctional Facility to protest years of mistreatment. Holding guards and civilian employees hostage, the prisoners negotiated with officials for improved conditions during a siege that lasted four days and nights.

When negotiations broke down, Governor Nelson Rockefeller sent hundreds of heavily armed state troopers, correctional officers, and other law enforcement types to retake the prison by force. That took no longer than a quarter of an hour but, by the time it ended, law enforcement officers had shot at least 128 men and killed ten hostages and 29 inmates.1 It was the bloodiest prison riot in American history, and it became a flashpoint, perhaps the greatest flashpoint, for the prisoner rights movement, at least in that country.

The public response was severe and, feeding into a growing anti-establishment sentiment, was quickly reflected in popular culture. Among many artists to deplore the loss of life and the prison conditions that led to the uprising, John Lennon penned a song, Attica State, in protest.2 It’s one of the first popular songs to call for us to “take a stand for human rights”. It also contained a few other lyrics that I thought were nicely rebellious when I first heard them such as, “Free the prisoners, jail the judges”, but I must say that I have become less fond of that as a notion in recent years.

Eventually, a batch of welcome reforms followed the Attica uprising, including the allocation of funding that allowed the first Prisoners’ Legal Service to be established along with several prisoner rights clinics across the United States.3

Closer to home, in New South Wales, riots at the Bathurst prison in 1974 followed by much of the same throughout a number of the state’s prisons, most notably at Long Bay, Grafton and Berrima,4 led to a ‘Royal Commission into NSW Prisons’ in 1976 which was headed up by Supreme Court Justice John Nagle.5

He went on a tour of jails in North America and Europe before undertaking a close look at NSW prisons. He was said to have been horrified by the conditions and the brutality. His report, handed down in 1978, was scathing. Taking the long handle to the Prisons Department, Justice Nagle described it as “an inefficient department administering antiquated and disgraceful gaols; untrained and sometimes ignorant prison officers, resentful, intransigent and incapable of performing their tasks”.

Justice Nagle made no fewer than 252 recommendations, the first of which was to sack the Commissioner for Corrective Services whom he found had “knowingly presided over a system that condoned the illegal use of force on prisoners”.6 Reflecting on his report many years later, Justice Nagle said: “I hope that it changed the attitude of the public to prisons; that people came perhaps to realise you can’t lock prisoners up and forget about them.”7 Notably, following the Nagle Inquiry, the ‘NSW Prisoners Legal Service’ came into being.

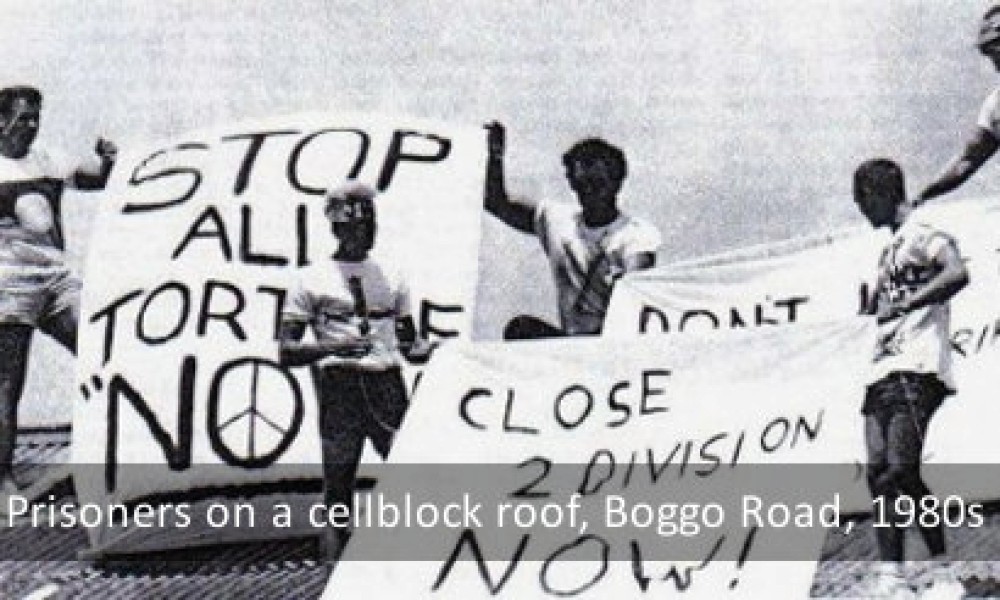

A rooftop prisoners’ protest in the ’80s. Photo: Boggo Road Historical Society (Inc.).

In Queensland, by the mid-1980s, Boggo Road was in a state of almost constant unrest. Riots, hunger strikes, and rooftop protests became commonplace. I recall for instance several clients of the firm where I worked being charged with the offence of mutiny, one of whom managed to fashion an eyepatch out of an old piece of linoleum and a length of string.

When produced for his committal hearing, he was wearing the patch and announced to anyone who cared to listen that, if he was charged with being a pirate, he may as well look like one. But like the sign at the gate, light-heated moments such as that were few and far between in those days, and nothing could obscure the powder keg Boggo Road had become.

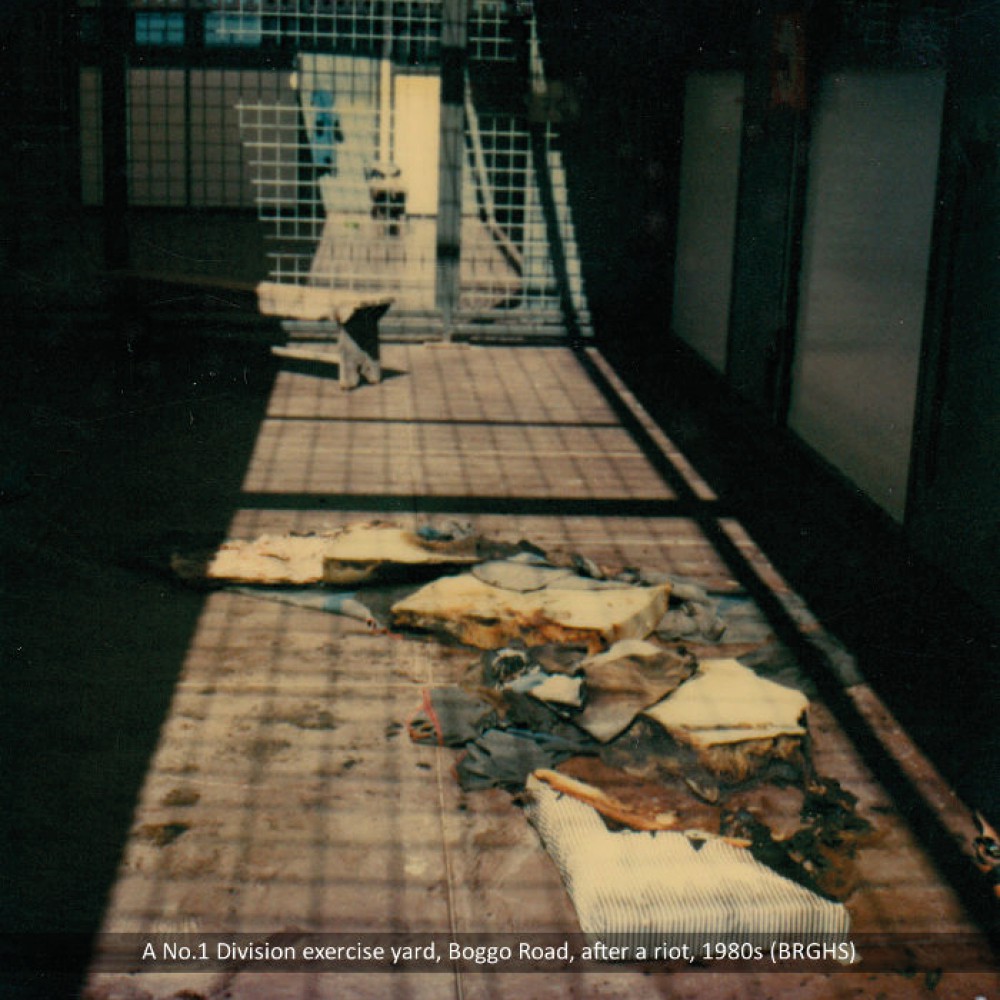

The ’80s saw the prison’s most turbulent years. Photo: Boggo Road Historical Society, (Inc.).

Now, I mentioned earlier that most of us practising in criminal defence worked with the system as we knew it. But to their enduring credit, not all were prepared to accept that system, or what went on within it. A small group of lawyers got together and decided to try to do something about it.

Tony Woodyatt was the driving force behind the group and he was ably assisted by Mark Finnane. Aided by Stephen Keim, Di Fingleton, Linda Anderson and Ian O’Connor, in 1985 they founded the Prisoners’ Legal Service (PLS), an entirely voluntary organisation, and by around the time the service was incorporated two years later, they were joined by several others including Jenny Cheney, Tim Reddell and Matt Woods.

Others such as Terry Fisher and, later, Lars Falcongreen, joined the ranks over time to assist the PLS for many years. And, as I am sure most of you will know, we are privileged to have both Matt Woods and Terry Fisher here with us tonight and, yes, in case you are wondering, Matt is still on the management committee along with, I should add, Lars.

Photo: Boggo Road Historical Society (Inc.).

Now these men and women, and those who followed in their footsteps, are the real heroes of this story. They did not walk past what they saw; they stopped and did something about it. For the first time, prisoners in Queensland had a voice, and a very effective one at that. Within a short space of time, and due in no small part to the advocacy of the PLS, the ‘Commission of Review into Corrective Services in Queensland’ was established in February 1988, chaired by Mr Jim Kennedy.8

He went on to preside over what in my opinion was one of the most efficient, and effective, inquiries ever to be conducted in this state. He produced two reports in rapid succession, the final of which was presented in August of that year. It was almost as scathing as the Nagle Report.

Among Mr Kennedy’s recommendations was one to the effect that Boggo Road should be demolished and, as it happened, No.2 Division was fully decommissioned by November of the very next year. The balance of the prison including the women’s prison suffered the same fate three years later. The Kennedy Report also became the catalyst for a brace of far-reaching reforms including a complete overhaul of the governing legislation and the establishment of the ‘Corrective Services Commission’.

Now more than 35 years on, the PLS has not only been responsible for bringing about much-needed reforms, it has performed a vital role in the provision of legal advice and representation for prisoners across the state and, through all the ups and downs in the criminal justice system of the past three or so decades, they have never lost focus on their prime objective, that is, to help people who are vulnerable in prison. Their charter may be expressed as simply as that, but as we all now appreciate, that has been, and will continue to be, an enormous undertaking.

These days, the work of the PLS is a broad church – from defending prisoners against human rights violations to guiding access to rehabilitation and other supports on release. It also collaborates extensively with other services to ensure that the needs of their clients are met. These include the Prison Mental Health Service, accommodation providers, community medical and mental health supports, NDIS advisors, and so on.

Along the way, the PLS has represented prisoners in relation to a whole range of cases before the courts, extending as far as the High Court, the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal and even the United Nations Human Rights Committee. Throughout, its law reform efforts continue unabated, the PLS regularly making submissions on proposed reforms as well as invaluable research such as a joint report with the University of Queensland on solitary confinement in Queensland that was released in May of last year.9

All 14 of Queensland’s prisons are served by the PLS. In the last financial year, one third of their clients were in northern Queensland prisons with the balance in central and southern Queensland. Prisoners have only a limited capacity to communicate with the outside – they can only access the mail and telephone.

To provide for this, and the increasing demand on the service, the PLS commenced a volunteer mail clinic last year which is staffed by law students under the supervision of volunteer lawyers. There is also a free telephone advice line which is operated twice each week to enable prisoners from across the state to obtain legal advice.

All of this is achieved through the work of just four lawyers – Principal/Director Helen Blaber along with Angelene Counter, Natalie McIntosh and Katrina Davidson – together with, most importantly, volunteer and pro bono support received from law students, members of the profession and members of the Bar.

Together they undertake a vast body of work with limited funding and in an environment where the demands on the PLS are growing at an alarming rate. In fact, they are now well beyond what can realistically be met. For example, in the last financial year, the PLS spent 400 hours answering telephone enquiries from prisoners but still missed over 50,000 calls, such was the demand.

As to this, there are several factors at play.

First, the overall prison population has increased by around 80% in the last decade. As of last Monday, 10,004 prisoners were held in correctional centres in Queensland with around a third of them awaiting trial. That number represents 132% of the built capacity of the existing prisons.

In short, our prisons are over-crowded and under strain, and that has been the case for some considerable time. There is also the sheer weight of numbers. To give you an idea about that, when I was visiting Boggo Road, the total population of that prison – men and women – was around the 400 mark, a world away from the numbers we are seeing now.

Second, we are of course in the midst of a pandemic and for different periods since March of last year, our prisons have been in various stages of lockdown.

Last, there are the much-publicised parole delays. As at 1 October, the Parole Board had a total of 4410 outstanding applications. Around half of those were applications for parole with the balance concerning outstanding parole suspension matters. The average time for an application for parole to be decided is currently 214 days from when the application is made but that is just the average, and we know that there are many cases where the applicant prisoner has been waiting many months longer than that. The PLS is at the frontline of all of this, attending to 1841 requests for assistance in the first nine months of this year alone.

Hardly any of the work performed by the PLS is particularly glamorous, but there can be no doubting its importance. A lot of the work that is carried out is unheralded, and often thankless. While that has probably always been the case, it takes a high level of dedication and professionalism to perform the work undertaken by the PLS and to stick at it.

For those like me on the outside, our obligation I think is clear – it is to support the PLS and these dedicated practitioners as much as we can through functions like these, financial assistance where possible and volunteer or pro bono work.

Although we have come a long way from the dark days of Boggo Road, in a very real sense the need for the PLS and our support of it has never been greater. So, with that in mind, thank you one and all for your attendance this evening to support such a worthy cause.

The Honourable Justice Martin Burns is a Judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland.

Footnotes

1 Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (Pantheon, 1st ed, 2016).

2 John Lennon & Yoko Ono (1972) Attica State – Some Time in New York City (Apple/EMI).

3 New York State Special Commission on Attica, Attica: The Official Report of the NYS Special Commission on Attica (1972).

4 Fiori Rinaldi, Australian Prisons (F & M Publishers, 1st ed, 1977).

5 New South Wales, Royal Commission into New South Wales Prisons, Report (1978).

6 Ibid.

7 The Hon. John Hailes Flood Nagle obituary. Sydney Morning Herald, 25 September 2009.

8 Commission of Review into Corrective Services in Queensland, Final Report, 31 August 1988.

9 Tamara Walsh, Helen Blaber, Claudia Smith, Lucy Cornwell, Karen Blake, Legal perspectives

on solitary confinement in Queensland [2020] UQLRS 8.

Share this article