Fact or opinion?

We take in much of what is happening around us as fact, rather than opinion.

We may take our boss’s words personally, making assumptions (opinions) about them and treating these assumptions as facts, for example, taking as a fact that they are ignoring us because they think our work is shabby or do not like us.

We may be reluctant to request a conversation with them to clarify our reaction or make a request for more information or support. As a result, we may feel resentful or anxious and take home that mood, affecting our family’s moods.

We call this ‘mood contagion’. If we had taken time to reflect and be curious, we may have noticed our boss appeared anxious because they were under pressure with the latest cost-cutting program or to make budget.

Examples:

My height is measured at 180 centimetres, a fact determined by agreed-upon objective criteria. Am I short, average, or tall? This is an opinion, potentially differing with each observer. A person of 150 centimetres may see me as ‘tall’, and a person of 190 centimetres may consider me ‘short’.

A person who is trapped in stress may not focus on my height. We see this in courts of law, where witnesses tell their versions of what they observed in a traffic accident. Unless a witness is lying intentionally, they will be telling their truth in the belief that their truth is what happened. In their eyes, they are telling the facts.

We are usually introduced to others, such as a partner, colleague, or client, before we meet them, through hearing others’ labels (opinions) of them. It could be ‘brilliant’, ‘not up to it’, ‘to be avoided’, ‘rude’, ‘a great mentor’, etc.

They become defined by that label, and it becomes their identity, the facts about them. We are often unable to see all the attributes making up the person and with our busyness may not take the time to distinguish between facts and opinions, and then test these opinions.

An exercise:

- Is there any aspect of your partner, colleague, or client that you may have considered a fact, but now see differently?

- If you now see it as an opinion, you may use the opinion test I offer below.

Reflecting on my years in law firms and corporations, I ask:

- What if I had tested my reactions (founded on opinions) to others’ behaviours?

- What if I summoned courage to make more requests of leaders I found difficult?

It would have saved me a lot of anxiety.

An opinion test

I offer some questions from Ontological Coaching to test our opinions. I use an example where, as a partner of a law firm, I think (have an opinion) Alex, a team member, is ‘lazy’. You may play around with this label using your opinion of a colleague or your boss.

For the sake of what am I having this opinion?

Asking ‘for the sake of what?’ takes me deeper than asking ‘why?’ It focuses me on my responsibilities, in this case, as a partner, prompting me to ask:

- What purpose is served by me having this opinion of Alex?

- Is my opinion more about me than Alex?

Language creates our realities. Labelling Alex as ‘lazy’, especially if made publicly, may be taken on by Alex and others as a truth, becoming a totalising description of Alex that diverts me and others from seeing their positive qualities. This may cause Alex to adopt a core negative self-assessment, such as:

- I am not good enough.

- I am not worthy.

- I don’t deserve success.

- I don’t belong.

Labelling Alex as ‘lazy’ may also tell me more about myself, including in relation to the standards I am applying.

From what standards am I having this opinion?

My opinion that Alex is ‘lazy’ may be informed by the standards of the social milieu of my growing up in Sydney. The father was the primary breadwinner, working hard to ‘succeed’, and ‘for his family’.

Fathers were trapped in the Protestant work ethic, not having time for problems. It was incredible for a father to show vulnerability and allow it in their sons. This is a generalisation, though exceptions came at a cost of being judged.

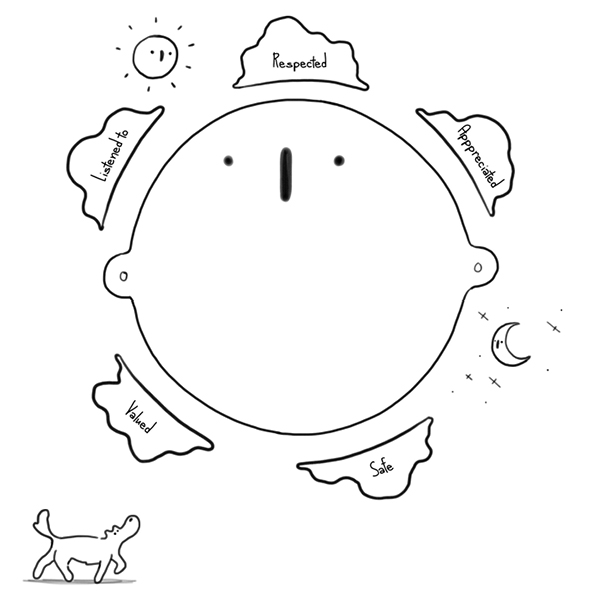

What about Alex? While I may have sought to free myself of the stories of my growing up, I must still pause to reflect on whether I am attending to what I call Alex’s core human concerns, allowing them to feel safe, listened to, appreciated, respected, and valued.

Our core human concerns – feeling safe, listened to, appreciated, respected, and valued. Drawing by Steve Bachmayer.

For example:

- While Alex may see their work as important, it is through a wider lens of living a holistic life.

- Alex may be neurodiverse, feeling comfortable when working in ways different to me.

- Alex may struggle with the blokey atmosphere I am role modelling.

While reflecting, I realise I have not sat down with Alex, in an unrushed and safe setting, to have a conversation that may allow Alex to articulate their needs and wants, to allow me to understand their standards. It may be that Alex is better suited to a different team, for example. This brings up another area of questioning, are there exceptions, that is, is Alex ‘lazy’ in all areas of their work and life?

Are there exceptions to Alex’s ‘laziness’?

In chatting with Alex, I may find other areas of their life, including their past work experiences, where they have not appeared ‘lazy’. It may be that Alex’s skill set and their general way of being would be better utilised in a different area of work, a different mix of people, or a different way of working.

It may also occur to me that Alex has only recently become ‘lazy’, and during our chat, I may realise Alex is having a tough time outside of the office. This may prompt me to offer time off.

In my conversation with Alex, I may ponder why they did not speak up, and make requests to me for a change. Before I discuss making requests, I offer an exercise.

Exercise:

- Think of a person you have difficulties with.

- Write down three traits about them.

- Are these facts or opinions?

- If an opinion, test it.

- Are there any actions that would be useful for you to take?

Making requests

In my coaching, I have found one of the most powerful questions to ask a coachee in solving an issue is, ‘what requests may you make?’ This is easier said than done. I will discuss making requests in the context of a case study involving coaching Judy to make a request of her boss, John (not their real names).

Case study: Making a request of your boss

Making an embodied declaration (commitment). Drawing by Steve Bachmayer.

At the end of a coaching session with Judy, she stood up, took on the pose of Libertas in the Statue of Liberty, and declared to me that she would make a request of her male boss, John, by 5pm the next day, for a four-day week for six months.

Judy declared she would let me know the result immediately afterwards. At about 3.30pm the next day, Judy called me. John had agreed. At the same time, he mentioned he was meaning to chat about a promotion for Judy and took the opportunity to do so. John also asked Judy to consider whether six months was sufficient to meet her needs.

It took Judy time to make her embodied declaration to request a meeting with John. In our earlier conversations, Judy told me how she felt extremely nervous with him. He appeared always to be busy, so she did not want to interrupt him.

She did not feel valued by him. I understood what power imbalance vibes John may be giving off, probably unintentionally, for you cannot change what you do not notice.

I made four observations to Judy around her untested assumptions (opinions):

- If you catch your boss in a relaxed space and are respectful and clear in how you make the request, the request will likely be well received. In this case, Judy planned the right time with John’s PA.

- What is the worst that can happen? Most likely that the request is not responded to or rejected, and the requestor is no worse off.

- The requestee’s off-putting behaviour is probably not personal. It is just their way of being at the workplace.

- If Judy’s request is dismissed without any discussion, it may tell Judy that it is time to seek other opportunities in the corporation/law firm or elsewhere.

Judy summoned courage to make this request of John, a man sitting in the power corner. Once made, the request acted as a call to curiosity, awareness, and action, prompting John to notice Judy’s concern and act on that noticing, taking the opportunity to chat with Judy about her promotion and display empathy for her need for a four-day week.

We may require support to build our courage. This also involves making a request and finding champions who may be our family, friends, or third parties, such as a sponsor at work or, as Judy did, a coach.

Exercise:

- Either as a boss or team member, does this case study resonate with you? Why?

- Are there any actions that would be useful for you to take?

Testing our opinions and making requests applies to all aspects of our lives. In my experience we rarely take time to sit back and test our opinions and reflect on what requests we can make to lead a more fulfilling life. I recommend you take time to reflect on the matters raised in this article, how they may be relevant to your life, and have a conversation with your loved ones, colleagues, or your boss about them.

Good luck!

Bill Ash practised as a corporate lawyer and executive for more than 30 years, and recently as a coach, after gaining post-graduate degrees in counselling and coaching. He has recently published a book, Redesigning Conversations: A Guide to Communicating Effectively in the Family, Workplace, and Society.

Share this article