Setting the scene 1: Trapped in my role

I am a partner of a law firm, married to Sally, with two children.

We rely principally on my income enabling us to have a comfortable house in an inner-city suburb, with two Tesla cars, and to frequent the in-restaurants, have overseas holidays, and pay private school fees.

The pressure is immense to keep up the client revenue. I feel trapped in the need to keep going. Out of the blue, a client offers me a corporate position ‘made for me’ that will be challenging, though allow me to have less pressure with a more structured lifestyle.

This client has had their share of ups and downs, with shedding of staff along the way. It will mean my income is substantially reduced. What do I do? I have a conversation with Sally.

Scenario 1: I am in resignation

I feel trapped in my income and lifestyle. I resist the offer and encourage a ‘but’ conversation with Sally:

But I may be made redundant, and I would need to start again … but we may not be able to travel as a family … but we will be required to rein in our lifestyle … but what will our friends say … but will our children cope?

I refuse to listen to Sally declaring her willingness to tone down our lifestyle and how she saw opportunities to ramp up her career. Our children have not yet entered high school and we are in a catchment of an excellent state school. Yet I insist our two boys attend my old elite all-male private school.

I am in a mood of resignation, resisting possibilities (our future).

Scenario 2: I move into ambition

Sally suggests we see a family counsellor. As difficult as it is for me, I agree. I realise we are not living to the full in our relationship with ourselves, each other, and our children.

Stress embodies me, infecting our family life. Sally steps around me, walking on eggshells, protecting the children as best she can. The counsellor encourages us to have a ‘yes/and’ and ‘why not?’ conversation.

Yes, let’s deal with my stress here and now and move to a more structured environment … and take it from there and explore other ways for each of us and our relationships to thrive … and have open conversations with our children, bringing them into the tent.

In other words, ‘Why not take up the offer to move into corporate life?’

I move into a mood of ambition, recognising there are other possibilities for me and ‘us’ (me, Sally, and our children), and I resolve to bring these possibilities about.

Setting the scene 2: A colleague is ‘unfairly’ promoted over me

I have an opinion that a colleague is unfairly promoted over me. I do not test this opinion (see my article on testing opinions).1 Rather, I oppose or resist what has happened. I shut off from my boss and colleagues and seek to undermine them. I am in a mood of resentment.

I move from resentment to acceptance to ambition

I discuss this with Sally. She encourages me to accept what has happened, that there is no point in trying to change something that cannot be changed. It takes a while for me to acknowledge there are other possibilities out there for me (ambition), and, with Sally’s support, explore them, making requests of others in my organisation for advice and opportunities. One comes my way, which I accept. I am thriving.

In Ontological coaching language, I moved from resignation to acceptance, where I paused and reflected, and then moved into ambition, supported by conversations with Sally. This was assisted by making requests of others that I discussed in my article on making requests.2

Moods and emotions3 are learning opportunities

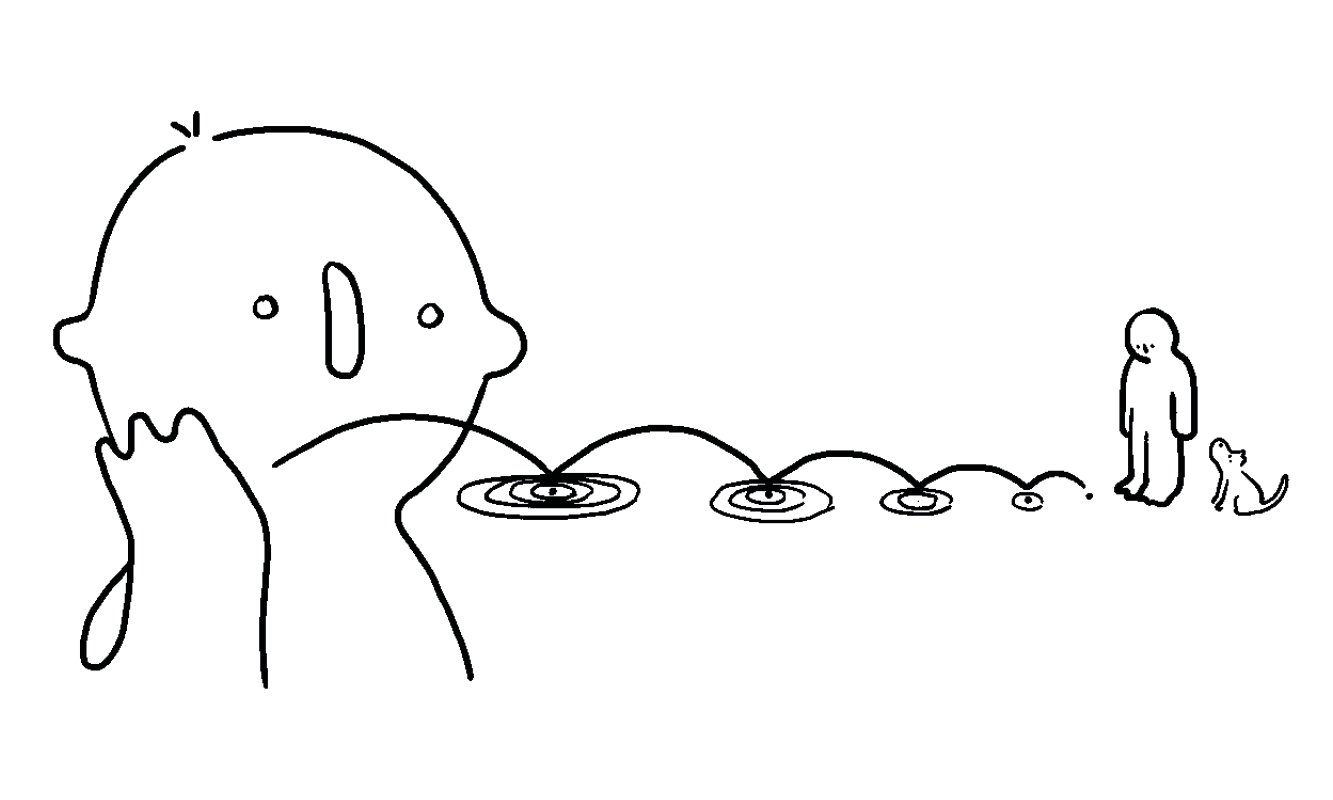

We carry our moods and emotions with us, affecting ourselves and others, akin to the ripple effect of a person throwing a stone (mood/emotion) out onto the water as in figure one, affecting the people around us.

Figure one: The ripple effect of our moods/emotions (mood contagion). Drawing by Steve Bachmayer

In neurological terms, this ripple effect is called ‘mood contagion’ and ‘emotional contagion’. It can have a substantial effect on the workplace and its bottom-line performance.4 In the examples above, I would have brought home the moods of resignation and/or resentment, affecting Sally and our children. Our children may have become anxious, taking that mood into their school.

Mood contagion includes helpful moods and unhelpful moods. For example, your boss may arrive at work, or you may arrive home, in a helpful mood, such as being peaceful, cheerful, or optimistic. Or you can bring to work or home an unhelpful mood, such as being cranky, gloomy, or pessimistic.

Our moods and emotions can trap us in adverse behaviours, such as lashing out at someone when we are resentful towards them. Or they can be a call to curiosity, asking, ‘Why am I angry?’ The answer may be quite different from what we first believed in the heat of the moment. For example, I may have reacted angrily to my partner, and upon reflection realised my anger was informed by not understanding (and acknowledging) the unpaid work they do at home.

The process of using our moods and emotions as learning opportunities can be a challenge. The archetypal man does not show his emotions or be vulnerable. Our protective nature acts against us allowing our children and team members to feel moods such as anger, guilt, and shame. It is a challenge for people like lawyers, who see themselves as espousing ‘logic’ and not emotions.

Yet to fully function as human beings, we must notice, manage, and learn from our moods and emotions. They are our greatest teachers.

There are numerous moods and emotions. I have mentioned curiosity, anger, guilt, shame, resignation, resentment, acceptance, and ambition.

A core skill in managing and learning from our moods is to test our opinions that I discussed in an earlier article.5 In the example I gave above of my boss promoting a colleague, it would be helpful to test my opinion that my colleague is unworthy of promotion.

Exercise:

- Is there any aspect of this article that has resonated with you?

- Would it be useful to discuss that aspect with your life partner, leader, or colleagues? This could include making a request for clarification to assist you in testing your opinion.

- If so, are you able to commit to take that step within a defined time?

In my next article, I will offer provocations to test our opinions in the context of ambition. I have chosen to focus on ambition given pressures on us to succeed from an early age, and the stress this can cause our families and workplaces.

All the best in crafting your journey.

Bill Ash practised as a corporate lawyer and executive for more than 30 years, and recently as a coach, after gaining post-graduate degrees in counselling and coaching. He has recently published a book, Redesigning Conversations: A Guide to Communicating Effectively in the Family, Workplace, and Society.

Footnotes

1 Having effective conversations: Testing our opinions and making requests, QLS Proctor.

2 Ibid.

3 I will use the terms moods and emotions interchangeably, though in Ontological coaching, which I follow, moods are emotions that hang around, becoming embodied within us, often out of our awareness.

4 Daniel Goleman, Richard E Boyatzis, Annie McKee, Primal Leadership: The Hidden Driver of Great Performance, Harvard Business Review, December 2001, https://wendyjocum.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/EI-article-3.1.4-Primal-Leadership-Realising-the-Power-of-EI.pdf, p1, viewed 1 June 2021.

5 n1.

Share this article