Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this article may contain the names and images of people who have passed away.

Today – 3 June 2022 – marks 30 years since the High Court’s landmark ruling in Mabo and Others v Queensland (No.2) (Mabo).1

The Mabo decision was a significant development towards the recognition of traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land rights under Australia’s common law, with the High Court acknowledging, for the first time, the existence of Indigenous land rights prior to, and following, Britain’s sovereignty over Australia in 1788.2

Significantly, the Mabo decision challenged the assumption that Indigenous Australians were “barbarous or unsettled and without a settled law”’ prior to settlement3 – an assumption that justified the importation of British law in Australia through the legal doctrine of terra nullius.4

In February 1986, the Mer Islanders, led by Eddie Mabo, challenged the constitutional validity of the Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act 1985, which “extinguished without compensation” any Torres Strait Islander claims to their traditional lands.

In December 1988, the High Court ruled in Mabo and Another v The State of Queensland and Another5 (Mabo (No.1)) that the legislation contravened the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). The decision in Mabo (No.1) enabled the High Court to begin hearing the original Mabo proceedings, the Meriam people’s land rights case.

In Mabo, the High Court ultimately agreed there was a concept of native title at common law, which entitled Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to the possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of their traditional lands pursuant to their laws and customs, provided native title had not been validly extinguished.6 Accordingly, the High Court declared:7

“[T]he Meriam people are entitled as against the whole world to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the lands of the Murray Islands.”

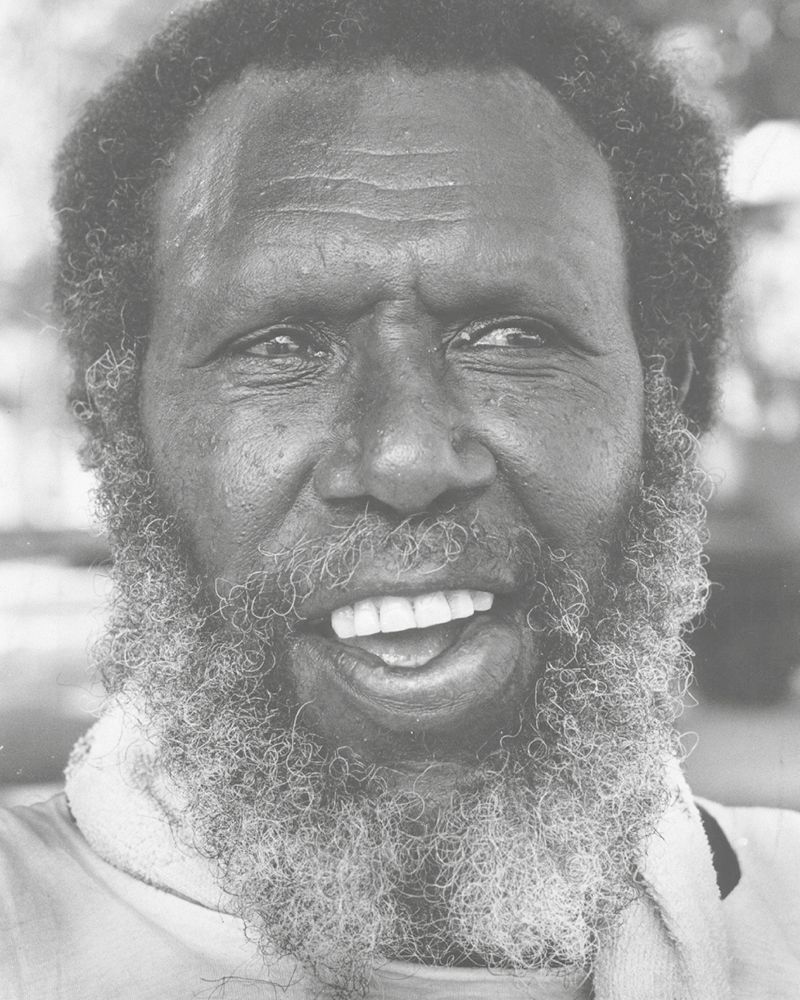

Bryan Keon-Cohen, Ron Day, Eddie Mabo and Martin Moynihan at ANZAC Park, Mer Island, May 1989. ©John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland Image No: 29122-0001-0020.

Although the Mabo decision was significant in promoting Indigenous land rights, there was considerable uncertainty following the High Court’s decision.8 The legal uncertainty that followed the Mabo decision prompted a legislative response in the form of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Act).9 Since the introduction of the Act, the concept of native title under Australian law has been narrowed by subsequent High Court decisions and amendments to the Act itself.10

Eddie Mabo

While native title has been recognised over about 32% of Australia,11 many have criticised Australia’s legislative response to native title as overly burdensome, especially the requirements of proof.12 Applicants must provide evidence of continued existence of traditional law and custom that gives rights to the land.13

Further, the land rights afforded to applicants pursuant to the Act are not exclusive; that is, to the extent of any inconsistency between titles granted by the Crown and native title, the Crown prevails.14

The Mabo decision was significant in changing social attitudes towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land rights. However, the High Court’s decision remains contentious 30 years on, with some maintaining the view that native title threatens private land ownership,15 a view that has been found to be baseless.16

As noted above, the laws governing native title impose a significant evidentiary burden on those seeking to have their native title recognised, making it difficult to substantiate a native title claim. Further, the most recent review of the Act concluded that a majority of native title claims are resolved by consent between the parties, as opposed to contested hearings.17 The legal realities of establishing native title stand in contrast to the view that native title threatens private land ownership.

While the Mabo decision was a major landmark in affirming native title rights, the High Court expressly denied any recognition of Aboriginal sovereignty.18 Accordingly, the Mabo decision has been described as imperfect in recognising Indigenous law and custom.19

The Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017) presents an opportunity to address some of the residual issues associated with the Mabo decision and Australia’s native title system. The Uluru Statement from the Heart asserts that Aboriginal sovereignty was never ceded and coexists with the Crown’s sovereignty today.

It calls for Aboriginal sovereignty to be recognised through constitutional change, in the form of self-determination rights. Without self-determination, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will struggle to overcome the legacy of colonisation and dispossession.20

The Mabo decision was the beginning of the process of addressing the legal injustices inflicted on Australia’s Indigenous people.21 Had the decision been handed down today, perhaps greater regard would have been given to the limitations of legislative methods in establishing sustainable and meaningful reform.22

As was called for in the Uluru Statement from the Heart, constitutional recognition and a First Nations Voice would assist First Nations peoples in obtaining substantive equality, which is needed to enjoy the right to self-determination.23

Although previous governments have been reluctant to establish a First Nations Voice to Parliament, the current Australian Government has recently pledged a referendum to constitutionally enshrine a Voice to Parliament.24

Nonetheless, the Mabo decision was significant in recognising traditional Indigenous land rights, and represents one of the many instances Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have used their voice to protect their kin and Country from the impacts of colonisation.25

Yale Hudson-Flux is a graduate solicitor at Queensland Law Society. Jaime Gunning is a Legal Assistant in the QLS Legal Policy Team.

Footnotes

1 (1992) 175 CLR 1.

2 Ibid [2].

3 Ibid [36].

4 Ibid [36].

5 (1989) 166 CLR 186.

6 (1992) 175 CLR 1 [2].

7 Ibid.

8 Supreme Court Library Queensland, Mabo v Queensland (No.2) [1992] HCA 23.

9 Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, About native title.

10 Shireen Morris, ‘The Torment of Our Powerlessness: Addressing Indigenous Constitutional Vulnerability through the Uluru Statement’s Call for a First Nations Voice in their Affairs’ (2018) 41(3) University of New South Wales Law Journal 629, 639.

11 Australian Trade and Investment Commission, Native title.

12 Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, About native title.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 ABC, Pauline Hanson says a lot of people been dispossessed of their lands due to the Mabo decision. Is she correct? (August 2019).

16 Ibid – Fact Checker found that Pauline Hanson’s claim is baseless as there are no native title decisions in Australia that have dispossessed a freehold land title holder of their land.

17 Australian Law Reform Commission, Connection to Country: Review of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (April 2015).

18 (1992) 175 CLR 1 [83].

19 Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, About native title; University of Melbourne, Marking Mabo: How has Native Title changed since the landmark ruling?

20 Australian Human Rights Commission, Right to self-determination.

21 Geoff Rodoreda, ‘Sovereignty, Mabo, and Indigenous Fiction’ (2017) 31(2) Antipodes 344, 350.

22 Australian Public Law, Consultation and a First Nations Voice: Building on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (March 2021).

23 Australian Human Rights Commission, The Declaration Dialogue Series: Paper No.5 – Equality and non-discrimination(July 2013).

24 Australian Labour Party’s response to the Law Council of Australia’s Call to Parties 2022.

25 Jason O’Neil, ‘Designing an Indigenous Voice that empowers: How constitutional recognition could strengthen First Nations sovereignty’ (2021) 46(3) Alternative Law Journal 199, 202.

Share this article