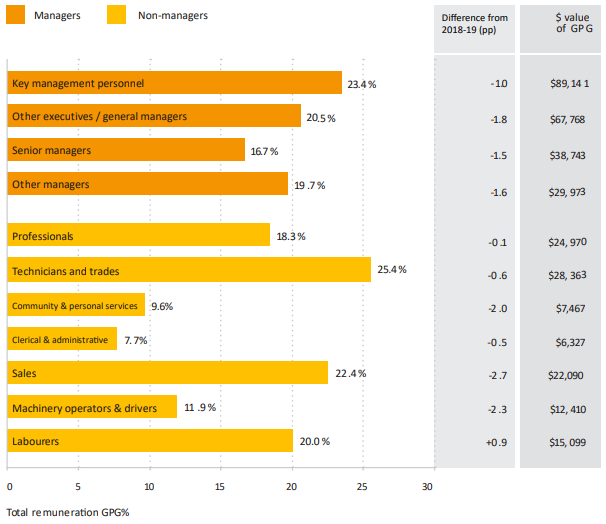

Imagine for a moment that you, your daughter, mother, colleague, or friend, is a female lawyer, working full-time, at a senior level (the equivalent of key management personnel). Then imagine discovering that male counterparts are receiving, on average, approximately $89,000 more per year, due to the gender pay gap.1

This statistic is an unfortunate reality for women across Australia, as demonstrated in recent data from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (Figure 1).

Compared to women aged between 40 and 49, male counterparts will also likely have around 30% more superannuation.2

Figure 1: Gender pay gaps by manager category and non-manager category (full-time employees, base salary and total remuneration)3

For women who have children, or plan to do so, add to this the financial and career impacts of maternity and carer’s leave, possible part-time work, job changes (for example, a potential move to an in-house government or corporate role) coupled with the chance that women in this category may accept a less senior/lower-paid role upon returning to the workforce to accommodate increased family and household responsibilities.

Dubbed the ‘superannuation gender gap’, this combination of factors, along with others, means that 23% of Australian women are reaching retirement age (60-64 years) with no superannuation at all4, one in three women (across all age groups) have no superannuation5 and, on average, women’s superannuation balances are about 30% less than their male counterparts.

Imagine that–almost one in every four women in Australia with no savings in the form of superannuation to support them in retirement.

But the challenge doesn’t end there. The substantial differences in superannuation balances between men and women persist throughout the working lifecycle.

Data from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) for 2016-2017 shows that, by retirement age, women’s median superannuation balances were 20.5% lower than those of men, but between the ages of 40 to 44 and 45 to 49, the gap was much higher, that is, 30.2% and 33.7% respectively.

With a significantly smaller nest egg to draw on, it is unsurprising that older women (55 years and over) have become the fastest-growing cohort of homeless people in Australia between 2011 and 20167 and that, according to AustralianSuper, ‘The Future Face of Poverty is Female’.8

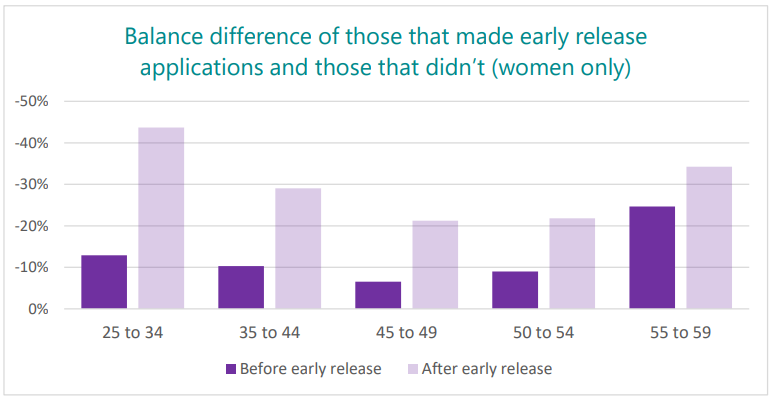

Of course, the issue of the superannuation gender pay gap is further complicated by the optional early release of superannuation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Women in Super ‘Early release of super fund data analysis’9, the early release of superannuation has further reduced the already lower superannuation balances of women across the country (Figure 2).

“For women who made early release applications, their already lower balances were further reduced. In the 25-34 year age bracket, women who made an early release application already had 13% less in their super than women who didn’t make an application. After early release, women who made an application had 44% less in their super savings than women the same age (Figure 2)10.”

Figure 2: Balance difference of those that made early release applications and those that didn’t (women only)11

“After these women took early release, the gender super gap increased to 51% for women in that age group12.”

The figure above illustrates the fundamental inadequacies in the use of super as a means financial stability in a time of economic upheaval and insecurity. It also highlights the long-term effects of the early release of super for women who are already at a statistical disadvantage.

The superannuation landscape highlights that poverty in retirement can be an issue for women from all walks of life, including in the legal profession.

In addition to identifying the shortfall, research provides us with important insights into the causes of this gap, and ways to address it, but we must act now.

In part two of this three-part series, Lesley discusses the cause and effect of the superannuation gender pay gap followed by potential solutions in part three. Stay tuned!

This article appears courtesy of the Queensland Law Society Equity and Diversity Committee. Lesley Symons is a Financial Crime Consultant, Subject Matter Expert at AMP and a member of the Committee.

Footnotes:

1Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), Australia’s Gender Pay Gap Statistics, February 2020. See: wgea.gov.au/data/fact-sheets/australias-gender-pay-gap-statistics. NB: This figure represents the difference in total remuneration at that level (as opposed to base salary) specifically to Key management personnel.

2WGEA and the Australian Government, Women’s economic security in retirement – Insight paper, February 2020, p6. See: wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Women%27s_economic_security_in_retirement.pdf.

3Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), Australia’s gender equality scorecard, p10. See: https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2019-20%20Gender%20Equality%20Scorecard_FINAL.pdf. NB: Based on total remuneration of full-time employees, which includes full-time base salary plus any additional benefits payable directly or indirectly, whether in cash or in a form other than cash. Includes bonus payments (for example, performance pay), superannuation, discretionary pay, overtime, other allowances and other benefits (for example, share allocations).

4Ibid, p5.

5Ibid.

6Ibid, p7. NB: This statistic applies across all age groups.

7Australian Human Rights Commission, Older Women’s Risk of Homelessness – Background Paper (2019), 4 April 2019, webpage summary. See: humanrights.gov.au/our-work/age-discrimination/projects/risk-homelessness-older-women.

8AustralianSuper and Monash University, ‘The Future Face of Poverty is Female – Stories Behind Australian Women’s Superannuation Poverty in Retirement’, 2019. See: australiansuper.com/campaigns/future-face-of-poverty.

9Women in Super, ‘Early release of super fund data analysis’, 2020. See: https://clarety-wis.s3.amazonaws.com/userimages/ERS%20Fund%20analysis%202020.pdf

10Ibid.

11Ibid, p2, Figure 2.

12Ibid.

Share this article