Besides being National Sorry Day, Wednesday 26 May marked another significant date on the First Nations calendar.

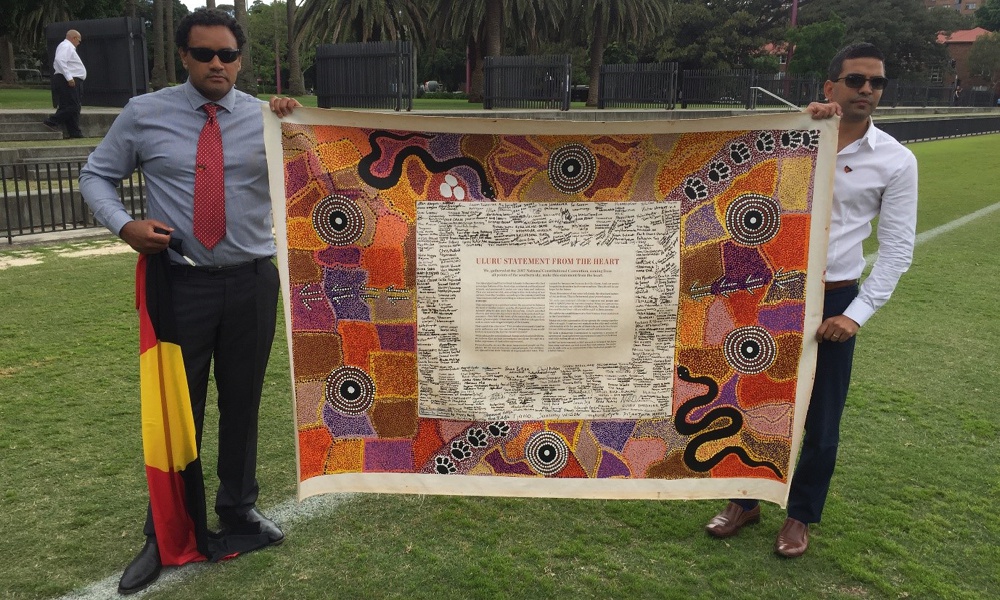

It was the fourth anniversary of the historic consensus of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, created by some 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates who formed part of the National Constitutional Convention in 2017. In their call for urgent Constitutional reform, the delegates put three direct proposals to the Federal Government – Voice, Treaty, and Truth.

Voice and Truth – Aboriginal deaths in custody

The themes of Voice and Truth resonated strongly through a event hosted by Queensland Law Society on 4 May, marking 30 years since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. The discussion panel provided insights and looked at potential solutions to address the issue of Indigenous deaths in custody. More broadly, it considered that a governance structure for Indigenous Australians was both desirable and appealing.

Path to Treaty

The recently announced Queensland Treaty Advancement Committee has been asked to make suggestions or consider options for the Government on what a treaty between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the Queensland Government may look like. Given the ongoing discourse on Indigenous disadvantage, one must ask whether a treaty would solve or mitigate the disadvantage faced by First Nations peoples.

Perspective on Treaty

I believe this is more than a legal argument; it is both political and cultural. It needs to be unifying and simplified, but we must look at the bigger picture of what is to be achieved when this proposal is put forth in the current climate of:

- the ‘Stop Adani’ coal mine movement, or

- the Black Lives Matter movements, or

- Constitutional enshrinement for a First Nations Voice.

Whilst it is commendable that there are discussions towards a treaty, I am genuinely concerned on the current path to Treaty.

To put it plainly, I believe a treaty would be a backwards step, unless First Nations people, in my humble opinion, are front and centre in this process. For the path to Treaty to have impact, to have ownership and support, there needs to be an elected body of First Nations people who makes decisions for us in this, and other, matters.

There many unknowns – what happens to native title landholders or the Native Title Act; will a treaty pose some inconsistency with the Commonwealth legislation?

The majority of First Nations peoples want land rights, and not a mere form of native title, which has so many limitations.

I also wonder if a treaty would be unworkable, because it wouldn’t be legally binding. First Nations people would assume that it was, but it would be a set of rules from an agreement under which each party ‘agrees’ to be bound, but not necessarily a legal instrument.

Currently, there are many initiatives on the list for advancing First Nations peoples in Queensland and nationally – whether by way of closing the gap, or creating a reconciliation action plan or employment opportunities.

We know and understand that there are underlying issues that needs to be addressed, that have already been outlined in the Tracks to Treaty commitment. These include a truth-telling process about First Nations peoples’ history, which is essential to my healing, our healing and the healing of the nation. First Nations people want genuine ‘self-determination’ (a phrase that has been loosely used, and becoming worn out.)

However, with the many initiatives for the advancement of First Nations peoples, I believe that a Voice enshrined in the Australian Constitution is new, fresh and something that this country requires for genuine reconciliation.

Proposal to endorse the Uluru Statement

We need a First Nations political structure to break the cycle of the disadvantaged faced by the majority of Indigenous Australians, to advance ourselves and, importantly, to understand what a treaty is actually going to contain without another surprise of disappointment or broken promises from the past.

I believe the Uluru Statement is the best way forward, because it’s a mechanism that will centralise all the initiatives for the advancement of First Nations people and communities. In addition, to being held accountable. While the colonial executive and legislative structure would always like to assist or work with us, it simply will not work until we as First Nations people can actually have the opportunity to have a good crack at controlling ourselves and our communities; look at the successes of our community-controlled services.

The nature and structure of what it will look like will at the very least give a degree of political power for First Australians, just like in Canada, in the United States and perhaps New Zealand.

The Statement contains the road map, which includes; “We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish…”

This is real ‘self-determination’ for First Australians in accordance with the United Nations Declaration to the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; “A right to self-determination… by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status…” (Art 3).

It will change the dynamics in the way the masses view us as Aboriginal people and give our younger generation a sense of pride and hope to be the change that is so required within any governance structure.

Read the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Joshua Apanui is a Bundjalung man (northern New South Wales) and a First Nations Cadet (Cultural Coordinator) at Queensland Law Society.

Share this article