The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has been the subject of many political and media discussions as of late, but those unaffected by the scheme may not appreciate the relevance of these discussions.

The NDIS represents a much a larger, systemic and structural problem with respect to access to justice.

For those unfamiliar with the NDIS, it is a scheme that funds costs associated with living with a disability. The NDIS was legislated in 2013 under the Gillard Labor Government and went into full operation in 2020. At the time, it was promoted as a world-leading program for people with disability.

There are two sets of criteria that a potential participant must satisfy to be able to access the scheme:

- Whether the individual is eligible to be a participant, and

- Whether the supports requested are reasonable and necessary to the person’s disability.

Once satisfied, funding is allocated to the individual, and the individual or their guardian chooses which providers supply the funded goods and services (subject to certain restrictions).

According to the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA), the statutory body charged with implementing the NDIS, it is intended that every NDIS participant has an individual plan that lists their goals and the funding they have received. NDIS participants then use their funding to purchase supports and services that will help them pursue their goals.

If a participant is unhappy with the plan provided, they can seek a review. If they remain dissatisfied following plan review, they can seek a further review of that decision. If, from the participant’s perspective, the issues are still not resolved, they can seek an external review by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT).

On 1 July 2020, the then Minister for the National Disability Insurance Scheme, Stuart Roberts, issued a statement advising that the NDIS was now available to all eligible Australians and the staged national geographical roll-out of the NDIS had been completed.

Fast forward (almost) two years. The latest NDIA quarterly report, released on Friday 6 May 2022, revealed that the number of people appealing NDIS decisions to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal had increased by 244% in the March quarter, compared with the same period in 2021.

While the NDIA maintains that these numbers are growing proportionate to the number of participants accessing the program, the statistics indicate that there were 1583 AAT appeals in the recent March quarter, compared with 460 for the same period in 2021 – an increase from 0.42% of overall participants, to 1.24%, and representing a whopping 244% increase in appeals compared to the same period in the prior year.

In the December 2021 quarter, the rise was even larger, with 1871 appeals representing a 366% increase on the 401 cases filed for the same period in 2020.

Keep in mind that, in order to appeal to the AAT, a participant must first have sought resolution through two sets of internal reviews. So, while the intention may have been for each NDIS participant to be provided with an individual plan comprising adequate funding to purchase supports and services that will help the person to pursue their goals, the sheer volume of applications seeking AAT review of an NDIA decision strongly suggests a disconnect between intention and reality.

The key issues

The reasons for such an increase in applicants appealing NDIA decisions may be debated. Whether the Government failed to appreciate the number of people who live with a disability (and would subsequently seek to access the NDIS) or underestimated the cost of living with a disability is a matter that requires more research. But the key social justice issue arising from this situation is:

- The number of appeals is increasing at an alarming rate.

- Government-funded organisations including community legal centres and designated advocacy organisations are unable to meet public demand for legal assistance and support.

- Due to a conflict of interest:

- Participants are unable to use NDIS funding to seek legal assistance or support.

- Support coordinators are precluded from assisting participants in circumstances where the participant is seeking additional funding for support coordination.

As a result, participants seeking appeals are often left to self-represent in the AAT against a Commonwealth agency that is regularly represented by some of Australia’s top-tier law firms. These applications are brought by persons with disability, or carers of persons with disability, some of whom may have to overcome access or communication challenges to navigate a complex legal process without legal assistance. The power imbalance is significant, and it is unconscionable.

This highlights two issues:

- The difficulty for people of moderate means to access legal assistance, and

- The lack of resourcing for participants engaging in NDIS litigation.

These issues are more concerning when reviewed alongside the guiding principles set out in the National Disability and Insurance Scheme Act. The governing legislation for the scheme states that people with disability should have the same right as other members of Australian society to respect for their work and dignity and to live free from abuse, neglect and exploitation, as well as the right to pursue any grievance.

How then, can a system guided by these principles, justify enabling circumstances where a person with disability who exercises their right to pursue a grievance is subjected to circumstances where they are being told not once, not twice, but three times, that their needs (albeit through a request for supports) are not reasonable or necessary?

What is the value or meaning of choice and control when publicly funded legal assistance providers are unable to assist? When an individual is faced with the decision to either represent themselves in opposition to a government agency represented by some of Australia’s top-tier law firms or use money they would otherwise use to fund their supports to hire a private lawyer in hopes of obtaining further funding for supports? How is someone subjected to this system meant to participate in community and employment in circumstances where they are unable to obtain funding for their day-to-day needs?

Call to Parties

Queensland Law Society has released the federal election 2022 Call to Parties Statement in anticipation of the federal election and has called on political parties to commit to specific actions to address some of these concerns.

In particular, QLS is seeking:

- A commitment to:

- urgently implement the remaining recommendations of the review by David Tune AO to improve the operation of the National Disability Insurance Scheme

- an independent review of the National Disability Insurance Agency’s management, use and costs of external legal practitioners, and

- increased funding for the continuation of the NDIS outreach program to reach potential NDIS participants based in remote and regional Australia, including in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

While the NDIS provides a good example of barriers to accessing justice for people with disability, it also highlights the importance of adopting an intersectional lens when viewing access to justice.

There are a variety of complex and intersecting factors which affect individuals’ capacity to access legal help. More often, an individual marginalised by one factor is more susceptive to being affected or prejudiced by another. These factors then compound to create further issues to accessibility.

That’s why QLS is seeking a review into the barriers to access to justice more broadly, such as access to affordable housing, healthcare and other support services.

These are not simple issues, but there are solutions. Government assistance and attention is one avenue; recruiting more private practitioners to offer low-bono and pro-bono support for NDIS appeals is another.

I encourage you to consider supporting clients with NDIS appeals and welcome you to contact legal aid, your local disability advocacy group, or me if you have capacity to assist.

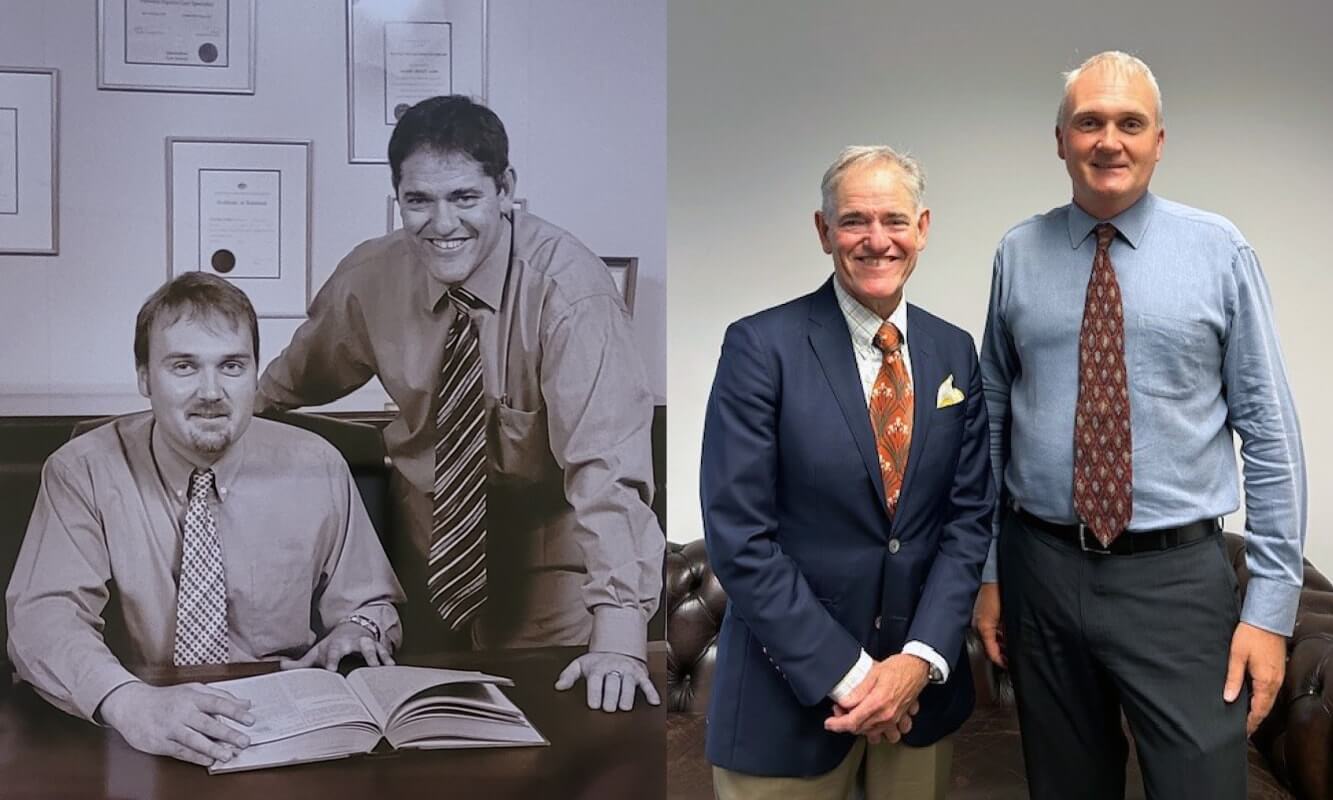

Sheetal Deo is Principal of Shakti Legal Solutions and a member of the Queensland Law Society Council. The views expressed in this article are those of the author.

Share this article