To most lawyers, Samuel Griffith is the jurist who drafted the Constitution, the Criminal Code, and many other laws, and who became Australia’s first Chief Justice.

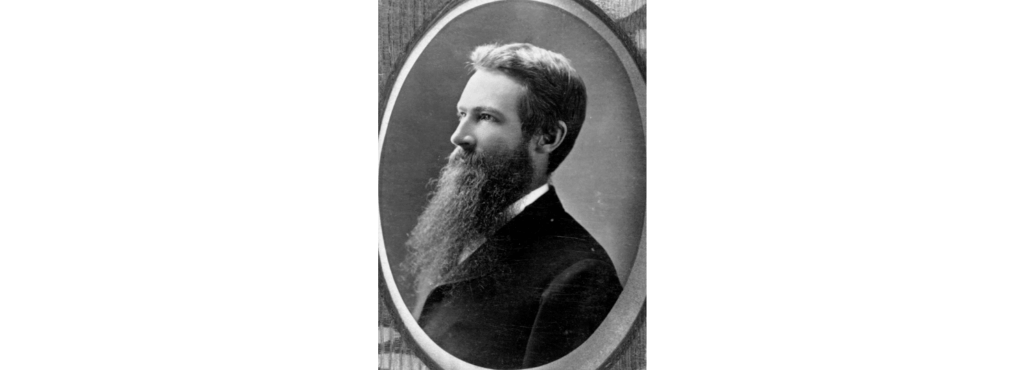

Portraits and photos of Chief Justice Griffith show a grey-bearded, austere figure.

Earlier in life, Griffith was many things: a precociously gifted student who went down from the bush to top Sydney University aged 17; a brilliant legal practitioner from the age of 18 with an unmatched work ethic; an idealistic, young, progressive MP who opposed vested interests and crusaded against the kidnapping of South Sea Islanders; and a more mature politician who, at the end of the his career, went into coalition with the conservative interests that he had earlier tormented.1

Griffith was not always a grey, old man. In middle-age, he was passionate, bright eyed, and sported a bushy black beard of which a modern hipster would be proud.

In 2020, 100 years after Griffith died, a seminar by the Australian Academy of Law and the Supreme Court Queensland Library touched upon some aspects of Griffith’s remarkable life. One of the speakers was the distinguished historian, Dr Raymond Evans, who spoke about Griffith’s Welsh origins.

As a young historian in Queensland in the mid-1960s, Raymond Evans began researching and writing about violence on Queensland’s frontier. Around the same time, another young historian, Henry Reynolds, was doing the same in North Queensland. Each pioneered writing and teaching in an area that had been ignored by universities, the media, and most of the public.

In 1975, Evans co-authored with Kay Saunders and Kathryn Cronin the ground-breaking book Race Relations in Colonial Queensland. His publications include A History of Queensland (Cambridge University Press). Decades after he started his historical research, Raymond Evans contributes to prestigious international works about genocide in Northern Australia.2

In 2021 and 2022, Henry Reynolds, in a book and then in an article in Griffith Review, accused Samuel Griffith of having prime responsibility for violence on the Queensland frontier during the time Griffith held office. In one flourish, Reynolds wrote that Griffith’s “neatly manicured lawyers’ (sic) hands were deeply stained with the blood of murdered men, women and children”.

These claims came as a surprise to Raymond Evans, who, while not a cheerleader for Griffith, had never seen Griffith as at the forefront of frontier violence by the Native Police or of having condoned it. Independently, other historians questioned whether Griffith was a suitable candidate for posthumous indictment for the crime of genocide.3

His curiosity aroused, Raymond Evans spent months in the archives, searching for the evidence and analysing it. The result is a remarkable essay “Samuel Griffith and Queensland ‘War of Extermination”. I cannot do justice to its development of the evidence, which shows that, far from supporting the excesses of the Native Police and some settlers on the frontiers, Griffith tried to mitigate the violence and prosecute offenders. Evans carefully explains the social and political environment in which Griffith, the politician, was constrained from doing more than he did to limit frontier violence.

If 19th century Queensland politicians are to be indicted for their blame in permitting frontier violence to occur, many would be indicted before Griffith. Evans presents a persuasive case that Griffith would not be indicted, let alone stand as a principal offender. For example, Griffith jointly led with John Douglas a progressive group that was unsuccessful in demanding a Royal Commission into the activities of the Native Police.

Evans elevates the analysis above selecting politicians for individual blame to a broader ‘systems analysis’ of the political, class and economic interests that drove the violent acquisition of land from Aboriginal people and the relatively few who ultimately benefited from their brutal dispossession.

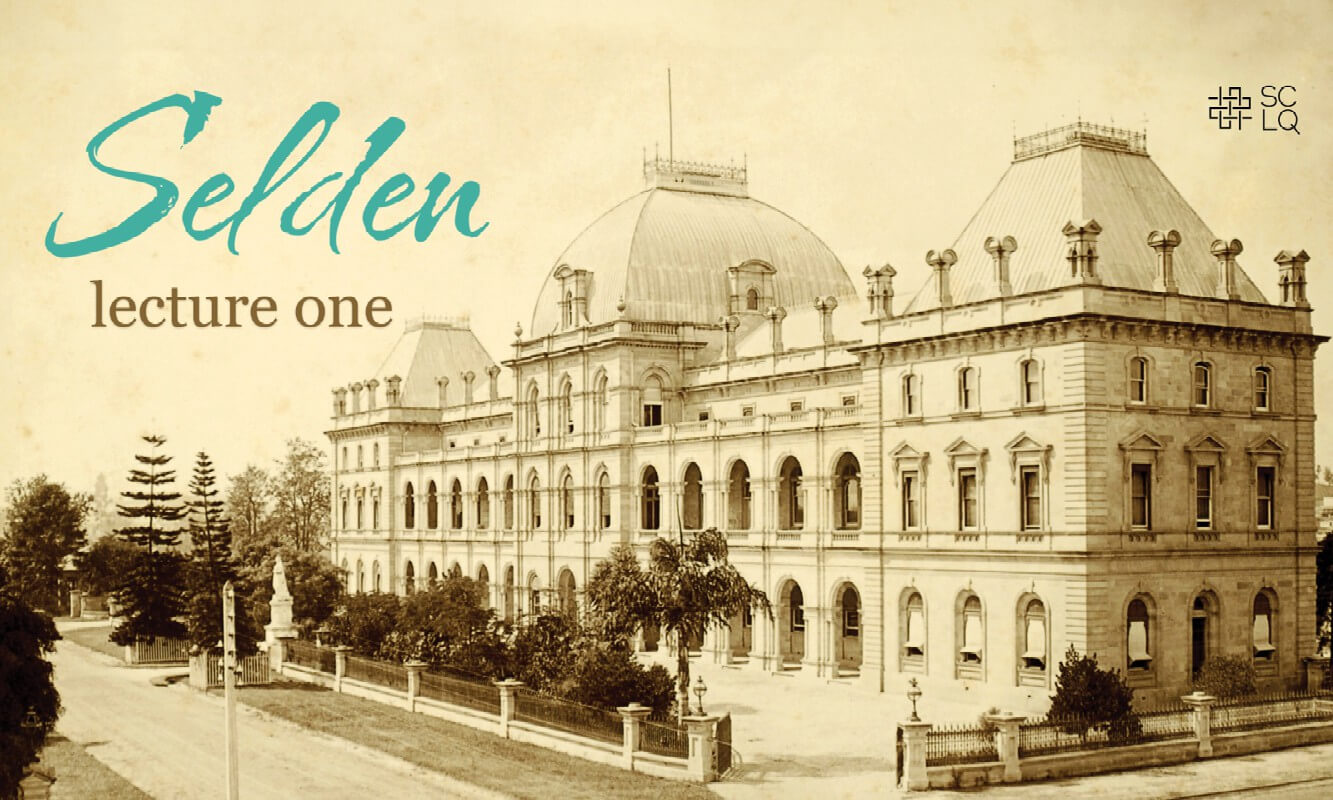

On Thursday 22 February, Raymond Evans will build upon his essay in the first Selden Lecture for 2024: The Rigours of Truth-Telling: Sir Samuel Griffith and Queensland’s Violent Frontier. The event is co-hosted by the Supreme Court Library Queensland and Griffith University. It promises to address the search of evidence, its analysis, and what “truth telling” by historians entails.

During the COVID-19 pandemic lectures had to be given on-line. Now we can attend the Banco Court in person and hear a stimulating lecture by one of our foremost social historians about one of our nation’s leading jurists. Please register to attend or, if you are unable to attend in person, register to view the live-stream starting at 5.30 pm on February 22.

Justice Peter Applegarth AM has been a judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland since 2008.

Footnotes

1 R B Joyce ’Sir Samuel Walker Griffith (1845-1920)’ Australian Dictionary of Biography (1983), https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/griffith-sir-samuel-walker-445.

2 B Kiernan (ed) The Cambridge World History of Genocide (2023) Cambridge University Press

3 Mark Finnane and Jonathon Richards, ‘S W Griffith: A Suitable Case for Indictment?’ (2023) 54(3) Australian Historical Studies 387.

Share this article